|

We’ve passed Samhain on the Wheel, and I’ve been thinking a lot about tradition. It doesn’t take a lot for me to arrive at the topic, but as I forage and tincture, chop roots and dehydrate leaf, I always wonder, what did they do before? When respiratory infections ravaged the mountains, how did people cope? It’s interesting to see all the herbal information being shared right now about COVID. So many great herbalists are sharing important information that we’ve gleaned from similar infections, as so few of us have ever treated anything like this before. COVID is a complex and serious infection, I look to old books and history not to replace modern medical care, but to ask the questions of how? And what? Our ancestors survived, and didn’t survive, many serious diseases. So I’ve been researching and asking, how did Appalachians treat these plagues that rolled through the mountains? Is there wisdom to be gleaned there for us to use today? How has treating upper respiratory infections changed in our tradition? Fevers in the Mountains: Appalachian folk medicine is, very briefly, a mixture of predominantly Indigenous, European and African folk healing systems within the cauldron of the bioregion of Appalachia. Shaped by the land forms, the weather, the plants, the fauna and the humans of this space, it is a unique, location based medical, and dare I say magical, system wrought from all its bloody, complex, and sometimes beautiful history. The unique climate and types of illnesses faced by Appalachians determined the ways that medicines were used, for those ailments most common could require the most diverse treatment options. Much wisdom rests in those old remedies, and while I write this as an exploration of a historical topic, I also wonder at how the remedies we are exploring today are not far off in some cases with the remedies of old. Chills and Fever: Many times, fevers and their associated chills would be caused by unknown or mysterious origins. This didn’t mean it didn’t need to be treated. Some herbs used are still touted as useful during fevers. Again I present this as a legacy of how peoples in this place have dealt with fever and this is not meant to take the place of medical care if one is experiencing serious respiratory symptoms or other medical issues. I think as herbalists, clinical or folk, it is good to know the legacies of medicine that has come before us to inspire, or mark the ways in which we have come to know what we do. +The Herbs+ They come from many traditions. African, Indigenous and European, plants from around the world now in Appalachia. +Boneset, which is sometimes called center weed in the Ozarks, was drunk as a tea for chills and fever. +Black pepper in brandy was prescribed for fever and accompanying chills. The use of pepper in Appalachian folk medicine comes from African folk traditions. +Ginger tea is good for fever. +Smoking dried mullein leaves is recommended as a cure for catarrh. Today I wouldn’t recommend smoking anything if you have phlegm, but for a long time folx have used smoke to move phlegm. +Sage tea is good for fevers. I use sage regularly for sore throat and general cold symptoms. Also as a steam. +Specific Illnesses and their Treatments in Appalachian Folk Medicine+ Malaria The ”ague” was used to describe chills and malaria in old herbals and notes in the backs of family bibles. Dogwood bark tea and tincture were used instead of quinine (peruvuian cinchona bark). They also used blue gin, which contained quinine as well. One of the most popular tonics and medicines in the mountains, wild cherry bark tea, was prescribed anywhere coughing, mucus and respiratory illness was present. This use was gleaned from Indigenous peoples who long relied on the bark as a Spring tonic and general respiratory cure. Anti-inflammatory willow bark and lung soothing mullein leaves were brewed into strong teas to combat the fevers and phlegm. The food plant corn was and purging all also used, fires burned to clean air of putrid matter Smallpox For this devastating disease, asafetida bundles were worn around the neck to ward it off. Sulfur in great amounts was burned in the house and worn in the shoes as well. Infusions of brandy and saltpeter was also used. Holly leaves and berries (which are toxic) were used as a tea. Black snakeroot or Black Cohosh tea (Cimicifuga racemosa), hot and cold treatments in water, and bathing in buttermilk. People applied Goldenseal salves to pockmarks to prevent scarring and infection. The toxic foxglove mixed with sugar was also used apparently successfully in the mountains. Tuberculosis, Consumption The main course was isolation and education. It took a while before people understood the ways in which to identify the disease as a unique condition and then note the way in which it spread. Sweating was encouraged with teas of solomon seal, fever weed, mullein, cow manure (yikes), along with a purging with jerusalem oak, wild cherry, sap of beech, hickory, sweet gum and or wild cherry. Anvil dust and molasses were also given. Rattlesnake meat was also used to combat the dread disease, as well as whiskey and salt. One would also sleep on a pillow of rabbit tobacco. The cherokee used skunk spray, ate skunk meat and used the scent pouch to ward away this illness. Typhoid Many people thought it was caused by poisonous vapors in the air (miasmic disease theory), and treated it with sweating, purging and puking. hot teas of ratsbane root (pipsissewa), pine needles, pennyroyal leaves, sassafras root bark, and lobelia. Ingesting a pill of pine resin the size of a bullet was also believed to combat thyphoid. Lime spread around the house, an almost magical barrier like cure. Pine knots were placed in drinking water, and onions hung on walls. Three messes of cooked Poke sallet eaten in spring was also taken to prevent it. Magical Methods of Treating a Fever "Climb a tree with your hands (do not use feet) and then jump off to leave your fever in the tree". "To cure chills and fever, knot a string and tie it to a persimmon tree" (No. 1094). "If you feel a chill coming on, get a toad-frog, or have one got, put it in a paper bag, and hold in your lap fifteen minutes. The chill will go into the frog. Then put him out on the ground, and he will shake him- self to death". (Frank C. Brown Collection of North Carolina Folklore.) For chills and fever, tie a piece of yarn taken from your stocking around a pine tree then walk around the tree three times a day for nine days For chills and fever, after you have had three or four chills, tie as many knots in a cotton string as you have had chills; then go into the woods and tie the string to a persimmon tree, turn around and walk away without looking back) — Ozarks: Randolph, 134 (knotted string around a persimmon tree). Drink a tea made of cherry tree bark for chills and fever. Wear a string of buzzard feathers around the neck to keep off the fever. Apple tree, dogwood tree, and cherry tree bark boiled into tea is good for fever. Split onions hanging in the house will keep off fever. To cure fever, drink boiled pine tree tops. A patient should break a pine top with (theri) face turned toward the setting sun, and make a drink from the pine top). Snakeskin bay and toad's eye in it are worn to ward off Works Cited: Frank C. Brown Collection of North Carolina Folklore. Randolph, 107. Thanks for exploring the wild world of Appalachian Folk Medicine with me. If you want to learn more about Appalachian folk medicine, magic, wild foods and plantcrafts, join Corby and I for next year's Hedgecraft program. Wishing you health and happiness in these trying times.

1 Comment

** A note to POC community. This post is aimed at providing resources for white herbalists and plant humans to do better. It may be exhausting to read. It also provides many links to POC herbalists, schools and teachers.** The world is on fire. Plague has ravaged the land. We are well into the Dog Days of Summer. And wow, P.S. these fires have been burning for a LONG time. Many white people are waking up to the fact that, surprise, there is still racism, and yes, it is a real thing. Many are learning that to be silent is to be complacent in the harm perpetrated upon Black people. It’s left many wondering how to help? What to do? Good news is, you don’t have to figure it out by yourself! POC have long been doing that labor, and it’s time for us to pay up. They have been telling us what they need, what we need to do better and how we need to show up. How can I help? What can I do? Those are very good questions. I wrote this post in an effort to compile some of what we can do as plant people, herbalists and Witches . Many people are saying, look to your strengths to find ways to help and to work within your sphere of influence to utilize your unique privileges to amplify Black voices, listen to asks around reparations and meet those asks, and do the necessary personal work to hopefully continue, or at the very least begin, the epic task of dismantling the racism that dwells within us. I’ve been asking myself as an Appalachian folk herbalist, forager and Traditional Witch, where is my energy needed here, where is it not, and what is being asked for that would be most helpful? I’d like to share all the amazing resources that others have done around these things and what we can do as plant people to ensure we are not continuing the same, extractive, colonizer, capitalistic, racist practices and address the gatekeeping and privilege that bar many POC from interacting with the medicine that was stolen from them. I know what I know because of those who came before. I live on stolen land, built by stolen people. First we must know our history. As herbalists we MUST know how we have access to the knowledge we do and WHY. It is hard and uncomfortable to delve into it, but that pain is little compared to the lived experience of the people whose stories we learn of. I believe it is our duty to understand and to really sink into that reality if we are to make medicine with plants on this land. Medicine County Herbs has an article on the history of medicine in America, and it is a great place to start. **Trigger warning** This article discusses the violent and racist history of American Medical Practices. If we are bioregional plant people, it is also of the essence to understand the history of the unique space you occupy. Who lived here first? Where are they now? What access do they have to their ancestral lands? I continue to be shocked by how many assumptions I make about all types of things. Myself, others, what they need or want. Often it’s not for me to wonder. I just need to listen. (If you’ve ever met me irl you know I am an ENFP and struggle sometimes to be a good listener). That doesn’t mean I get a free pass! It’s important to slow down, and start deeply listening. I ask myself, why does this particular point a person brings up challenge me so much? Why does a point NOT challenge me? By reading and listening about how colonialism and the mindset it has created treats POC herbalists and healers we can feel into those uncomfortable places and do the hard but necessary work to ensure we are not continuing to enact those practices. Also we can see that white people don’t have to set the table, we just need to frikkin let POC have their own and support them in doing that their own way. Check out ways to heal your own ancestral wounds. In my work, I focus heavily on sharing folk magic and witchcraft traditions from Irish, German and English histories, because those are the three largest ancestral connections I have. Learning about the folk medical and magical practices of my own ancestors has helped me hold space for and resist culturally appropriating marginalized peoples medicine to fill a void I feel within myself. Via Hedera, one of my favorite fellow animist witches, makes a great point in her podcast interview on New World Witchery that honoring or mentioning the magic and medicine of others is not the same as claiming it and appropriating it. This also means that when I teach about Appalachian Folk Medicine and Magic history, I do the research and put in the time to see whose medicine we are talking about. Cayenne peppers? From Africa. Using rice to keep away evil spirits? Folklore from enslaved black people. All the times I speak about native plants and how we use them, I try and find out which First Nations in our bioregion used/are using these plants and how we came to have them in the pharmacopoeia today. This is not the right way to do things. I don’t know what that is, and I want to try and find the ways to get closer to what that looks like. Say where things come from. It’s important to fight against the whitewashing of history. Support living people who are the ancestors of these traditions you benefit from. This is a true joy! If we go way back, all our ancestors did cool stuff with plants at some point! Uplift other’s journeys to practicing and reclaiming their own ancestral traditions as an ally rooted in the arms of your own often diverse ancestors if you can and have access to that information. This work really helped me identify ways to further decolonize my own ways of thinking and even validating herbal information and research!

How can we Help? Help by donating. This is, if you are able to financially, important and helpful, and honestly it’s really the least we can do. Here are some great places to place your dollars. Remember these are just a few of the many options, so also do you own research! Reparations is an important and vital part of striving for an equitable world. Read more about why this practice is vital here. There are ways already in place to begin this work, check out what Soul Fire Farm has set up. This is not charity, it is necessary. This list is totally not complete, I’m happy to add any more resources or links if you feel like sending them to me! Rootwork Herbals Provide $$ for POC to attend this beautiful POC run school in upstate NY. The Charlotte Herbal Accessibility Project Provide support to get medicine to those who need it most in Charlotte NC run by a wonderful human named Brandon Ruiz. Community Health Herbal Network “Community Health Herbal Network is a network of communities in the South that offer free herbal care, education, and wellness services that are geared towards the preservation and re-cultivation of the widespread and sustainable uses of herbs. Our resources are dedicated to our elders, our ancestors, our communities, and all those harmed by land and resource colonization, environmental racism, war, ableism, homophobia, transphobia, classism, sexism, addiction, the prison industrial complex, and the medical industrial complex.” Hawthorn Collective here in my own town, Asheville NC. Donate medicines or first aid supplies. Reparations with La Yerba Mala Herbs Schools Run by POC and POC Herbalists: Rootwork Herbals, NY *A great resource list: POC Herbalists to Support and Follow list from Queering Herbalism plus many more links to important Queer and Trans resources Hood Herbalism, CA Omaroti, Puerto Rico Ancestral Apothecary, CA Seed and Thistle Apothecary, You can support their BIPOC scholarship fund here La Mala Yerba NCB Schoolof Herbalism, GA Herb Schools that offer POC Scholarships: Old Ways Herbals ,VT Common Wealth Herbs, MA Wild Faith Herbal Wellness Mutual Aid Herbalism Solidarity Herbalism Anti-Oppressive Learning for us All Herbalista’s Links List is Amazingly Helpful! This is a lifetime of work. Please keep on keeping on. Care for yourself so we can care for each other. Everyone needs access to their medicine. It’s Spring. The last few days have been a blur. Here at the Hawk where I live, we have been practicing social isolation for almost 3 weeks and now, we are staying home with the “stay at home stay safe” declaration…. with 13 people. I live in a community of 11, and two of our friends who live alone have joined our clan here on the 24 acres we dwell on. It’s wild. This time has brought to light all the holes. The holes of our preparedness, our supplies, our interpersonal relationships, and our skills. People have been messaging me a lot about herbs, about wild foods, and even to delight in the strange posts I make each day of our lot’s throat singing fights and wrestling matches in our common kitchen. How to feed ourselves? Each other? Well I know we are far from being able to totally support ourselves nutritionally from wild foods alone without prior prep, but they can really help meet our nutrition and calories needs in lean times (and well, all the time). If you need any more convincing check out the sweetest people here at Gather Victoria and their case for wild foods. In this time, when work is gone for many of us and money is a looming question, myself included, I am comforted by wild foods. Knowing that there are essential nutrients bursting from the ground right now in sudden and near chaotic abundance is deeply comforting. My partner and I have been putting up venison, bear, and nuts this last year, and so we have our fats and proteins down, but all the other calories, where could we find them right now? If the store was out of food? If we had no more cash? These are the questions we’ve been asking each other and so I want to give you the beginning of a foraging basket. Here are some easy to find, important wild foods out in abundance right now that can help ease the burden that are not just wild greens (but let’s be real a lot of them are). Day lily: (Hemerocallis fulva) Native to Asia, this beautiful flowering lily has escaped cultivation and spread throughout the US. The flower buds are known as “golden needles” in China and are sold as ingredients for soup. I love these because they are abundant, and almost every part of the plant is edible. I also like to think about how foraged foods fit into my diet, and how one cannot live on greens alone. The tubers of these lovelies provide a prolific, easy to harvest and even grow, wild carbohydrate and rich calorie source. The young shoots and leaves are edible raw or cooked until they begin to get fibrous as they grow taller. Beware, however, Iris (toxic to eat) can look a lot like daylily so always be VERY sure you know what you are harvesting. Also, like with all wild foods, some folks are allergic, so always try a small amount of a new food before going hog wild. Here more info also on the edibility questions of the 60,000 ish varieties that have been bred! I only eat the orange, naturalized species, Hemerocallis fulva. I’ve watched the same patches for many years and know which variety grows there. It’s just one more way to become more intimate with your bioregion. I like to either boil and mash the tubers and then fry them into something like a latke, or saute well and season with the next plant on our list and butter. Later in the year the leaves can be used to plait into useful things. They are a wonderous plant. Onion Grass (Allium vineale): Blend up this abundant wild grass with salt and dehydrate or dry and sprinkle like store bought dried onion on, well, everything! This common “weed” is the reason the yard smells like a restaurant every time the lawn is mowed in Spring and Fall. A lover of cool weather, I eat these until they fade away in the heat of Summer and again when they return in the cool of the Fall. I really enjoy the bulbs if you dig down, they can sometimes be as big as a quarter. I’ve loved pickling, lacto-fermenting and drying these lovelies. I also just use them in almost every savory dish I prepare. I often notice them growing up over the grass, as they grow more quickly, and notice they have a tubular leaf, not a blade, accompanied by their strong onion smell. Ramps are a celebrated spring wild food, but so are the humble wild onions which are much easier to find and also not endangered. Dave Meesters and Janet Kent at Terra Sylva have been providing information on herbal anti-viral protocols to the wider community and with that gave a great recipe for “Honion”, or onion syrup. I have made some wild onion syrup in the same spirit for breaking up stuck phlegm thanks to their inspiration. Chop the bulbs of the onions fine, place in a clean, dry jar. Cover with honey and infuse 3 - 5 days stirring with a clean spoon occasionally. Place in the refrigerator and it should keep 3 months. Take liberally as desired. Check out their work for more important information on a wide variety of herbal topics. Chickweed: (Stellaria media) This abundant nutritious food and medicine is going to flower right now and ending its growth season a bit early this year with this warm Spring. We gather big handfuls with scissors and blend it up in pestos and green dressings. We also just chop it fine and eat it by the forkful as a base for our wild salads. The mineral rich taste, the little white flowers, it is one of my favorites. Here’s a sweet video on how to ID it. Nettles: (Urtica Dioica) Nettles are just perfect to eat right now, and wow are they a vibrant shade of healthful, brilliant green. They are naturally high in silicon which is great for the hair and skin. They contain 6500 I.U.s of Vitamin A in a 100g serving! They are also surprisingly high in protein at 5.5 grams per 100 grams. They contain 33.8% crude protein, which is quite high for a plant source. It’s best to eat these, rather than make tea, to get everything you can from these powerhouses of nutrition. Steam them, stew them, or fry em up in butter. They also contain calcium, chromium, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, vitamin A, B1, B2, B5, E, K1, choline, folic acid and zinc. It also has extremely high protein content. Stinging nettles even has vitamin D, which is rare in a plant source. Vitamin D is found mostly in mushrooms, but from very few plants. Its’ high iron content is what makes nettle ideally suited for people with challenges to their immune system and low energy. Nettle is appropriate to use to prevent infection and recover from infection, but since bacteria needs iron to spread, it is best to stay away from iron rich food until the infection recedes. It’s also a diuretic, making nettle is a helpful wild food for people who often struggle with urinary tract infections. It’s often combined with dandelion leaf or chickweed. Any herbal treatment of PMS or swollen ankles is greatly enhanced with a dose of nettle. Stinging nettle is also a blessing for any one who suffers from allergies. Its secret lies in the nutritional boost it gives the body as well as the anti-inflammatory action of its leaf. Nettle is usually thought of as relief for pollen allergies but recent studies have concluded patients with skin conditions such as eczema and hives benefit as well. Nettle root increases the production of T cells, which is vital to controlling allergic reactions as well, so the leaves are not the only useful part. A dose of nettle before meals can even help people with mild to moderate food allergies as well. I love to saute the leaves and make quiche, frittata or just plop a fried egg on top of a mess of the cooked greens and call it breakfast. I also blend them into pestos and smoothies, just make sure you really blend them well to avoid a sting! Dandelion: (Taraxacum officinalis) This hated lawn invader should really be celebrated for its divine nutritional content. Lowly dandelion, we are not worthy. It is very high in dietary Fiber, Vitamin A, Vitamin C, Vitamin E (Alpha Tocopherol), Vitamin K, Thiamin, Riboflavin, Vitamin B6, Calcium, Iron, Potassium and Manganese just to name a few. Easy to find and ubiquitous, the roots are also excellent as a liver support tea, and taste delicious toasted as a coffee-like beverage. The roots are also edible when young and can be diced and spiced in the stirfry pan. They are rich in inulin, a prebiotic which aids gut health. What’s not to love? I like to harvest the blossoms, batter them in whatever flour you like and fry them up, dip in honey and call it a magical day. Dandelion blossom fritters. I use chestnut flour from last fall ground very fine and eggs from our chickens, it is divine. The greens are quite bitter but when mixed with the other greens mentioned here, they can add a complex flavor. I find adding a tasty vinegar helps to soften the bitter blow. I have also been making dandelion blossom wild soda by mixing dandelion flowers, honey and water to taste and letting it ferment in a clean jar in my kitchen. A joyous treat and basically like drinking the Sun. Dead Nettle: (Lamium purpureum) Dead nettle, red nettle or purple nettle has manninotriose, a storage carbohydrate that has prebiotic, antioxidant and immunostimulatory properties. Despite it’s bad-tasting reputation, when properly prepared, it can be a delicious addition to spring wild food dishes. Dead-nettle's reported to be highly nutritious, abundant in iron, vitamins, and fiber. The oil in the seeds is high in antioxidants. And the bruised leaves can be applied to external cuts and wounds to stop bleeding and aid in healing. Dead nettle is a good source of flavonoids including a special one called quercetin. Purple Dead-nettle can improve immune system performance while reducing sensitivity to allergens and inhibiting inflammation. It’s also useful for anti-allergy applications due to the concentration of flavonoids. This is what helps their ability to reduce the release of histamine. You can make a tea from this tasty plant as well for allergies and histamine issued. Externally you can mash the leaves so they’re bruised, and apply them to minor skin abrasions and wounds. I love these chopped very fine, mixed with egg and wild onion, and fried up as a little fritter. We call them Dead Nettle Eggy Fritters. They are divine. Violet: (Viola spp.) This beautiful common wild flower has edible leaves and flowers. With over 400 species, it’s great to know that they are all edible. Famous old school forager Euell Gibbons found per 100 grams fresh leaves contain 210 mg vit C (4.5 x oranges) and 8258 IU of provitamin A. More recent analysis shows that if collected in spring, this early research reported that violets contain twice as much vitamin C as the same weight of orange and more than twice the amount of vitamin A, gram for gram, when compared with spinach. One recent study concluded that an aqueous Viola extract (i.e. tincture) inhibited the proliferation of activated lymphocytes as well as negatively affecting other hyper-responsive immune functions. This indicates that violets may be useful in the therapy of disorders related to an overactive immune system. Violet leaves contain a good bit of mucilage, or soluble fiber, and thus are helpful in lowering cholesterol levels. Soluble fiber is also helpful in restoring healthy populations of intestinal flora, as beneficial bacteria feed off of this type of fiber. The leaves are high in rutin, which is a glycoside of the flavonoid quercetin. Rutin has been shown in animal and in vitro studies to be anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, and blood thinning. Many foods that are high in rutin, such as buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum), are eaten traditionally as a remedy for hemorrhoids and varicose veins. I chop the leaves fine and add them to salads (beware, too many violet leaves are an effective laxative). I LOVE the flowers. I make a syrup every year. Check out my older post on violet for more info on one of my favorite plants. Fermented Wild Greens I was told that you can’t make tasty wild greens, so of course I tried it myself. I say just grab whatever is around I use nettle, violet, chickweed, dead nettle, wild onion and toothwort leaves. Wash the plants, drain them, chop them fine, place in a big bowl. Then add salt (2% – 3% of weight of fresh plant), mash up well with hands, let stand 20 minutes to draw out the liquid. Pack in jars small jars, leave to ferment 1 week in a cool, well aerated place and enjoy. Make some today to enjoy at Ostara and mix a few tablespoons of this salty connection into a few cups of yogurt to make a local “tzatziki” sauce. For exact instructions see this fantastic article. There are a LOT more foods out right now, but these are the ones we are eating the most of right now. Remember again to NEVER eat a plant without exact identification and always ASK if you are unsure! So my friends, take heart in the wild world if you can and know that there is much around us. I hope you are finding nourishment in this uncertain time, which for many, is how it always has been. The old structures will have to crumble, they are built for destruction. Works Cited ------------------- Adhikari, Bhaskar Mani, Alina Bajracharya, and Ashok K. Shrestha. “Comparison of Nutritional Properties of Stinging Nettle (Urtica Dioica) Flour with Wheat and Barley Flours.” Food Science & Nutrition 4.1 (2016): 119–124. PMC. Web. 20 Mar. 2018. Dos Santos, Raquel et al. “Manninotriose Is a Major Carbohydrate in Red Deadnettle (Lamium Purpureum, Lamiaceae).” Annals of Botany 111.3 (2013): 385–393. PMC. Web. 21 Mar. 2018. Rutto, Laban K., Yixiang Xu, Elizabeth Ramirez, and Michael Brandt, “Mineral Properties and Dietary Value of Raw and Processed Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica L.),” International Journal of Food Science, vol. 2013, Article ID 857120, 9 pages, 2013. doi:10.1155/2013/857120 www.chestnutherbs.com www.eattheweeds.com January 17th has come and gone, and to some is known as Old Twelfth Night. In 1752 the calendar was changed, and Twelfth Night is now January 6th, also known as the Feast of Epiphany, but to those who follow the old calendar, it would be this eve that Wassailing orchards and other festivities would be observed. We’ve talked about the magic of wassailing here, but tonight I want to pay homage to a strange and special plant that never touches the Earth. Though Christmas has passed us, Mistletoe, Viscum album, has long been a powerful magical plant of the Yuletide season and the Winter months. It’s name comes from the Old English misteltãn. This parasitic plant that grows on various trees, particularly the apple tree, it is held in great veneration when found on Oak trees, which is often rare. Perhaps it is the rarity of it that has caused it to be held in such high regard by so many cultures. As a parasite that growths in neither sky nor earth, it has long held a reputation as a magical plant. A powerfully protective plant, both heralded as a protection against and of witches and magical practitioners, I find it to be indispensable from the Magical Herbaria of Winter. Since we’ve passed Twelfth night or January 5th- 6th, now it is time to deal with the remnants of the Winter Solstice celebrations and decor. In some traditions, it was on this night that the mistletoe would be burned, in others it was wrapped and secreted away to come out again for the following year. The most notorious folklore I’m sure almost everyone has heard, is that it’s best to kiss beneath the mistletoe. Peter Haining in his book 'Superstitions', "The mistletoe, was revered by the ancient Greeks as sacred, yet superstition has it that the reason why it is so lucky to be kissed under it is that the plant once offended the old Gods, who thereafter condemned it to have to look on while pretty girls were being kissed!" The origins of the associations with kissing and mistletoe are murky, though the role mistletoe played in the story of Baldur from norse legends may have something to do with it. It is said he was beloved above all other gods, and his mother Frigga, loved him best of all. Fitting, for she is the goddess of love and beauty amongst other things. She feared for the harm that life could bring Baldur, so she went about the land securing promises from all beings that they would not harm her son. But of course, there was one that was forgotten, mistletoe. Loki, the ever wicked trickster and ne’re do well of the ancients, made an arrow of the wood of the plant and convinced a blind god, Holder, brother of Baldur, to shoot it at him. Loki directed the arrow at Baldur’s heart and it struck him and killed him. There are multiple endings to the story and the strange translucent, white berries of the mistletoe can be seen as Frigga’s tears. If the story ends happy, Baldur is restored back to life and the love Frigga has long been associated with meant all who stood beneath this powerful plants would be bestowed with a kiss. In Holstein Germany, the branch is called “the branch of spectres” and is thought to cure fresh wounds and give luck in hunting. It also keeps away both thieves and werewolves. If not mistletoe could be found on oaks in the old days it was an ill omen. To see if the one you love will marry you, there is a charm you can do with the leaf of the Mistletoe. Take one leaf of mistletoe and name it for yourself and one for your sweetheart, draw a circle before the fire and place yours in it, and if he is to marry you, the leaf named after him, which you place outside the fire, will jump into the circle. In the Ozarks, it was believed to keep witches off the meat in the smokehouses, while in Normandy it would de-flea featherbeds and protect young children from being whisked away by fairies. In Staffordshire, a sprig of last years mistletoe burned under this years pudding would carry Christmas luck forward. In Italian folk magic, women would carry a sprig of mistletoe to ensure conception. It seems that mistletoe is usually up to the task. In Wales it was believed that a sprig of mistletoe gathered on St. John’s Evening would induce dreams of omen both good and bad. In Sweden, a ring of mistletoe will ward off sickness. It is also used as a protective talisman against fire and lightning when hung in a barn or house. It is also said to open all locks. It remained sacred to the Druids from many accounts and this regard was so high, that mistletoe was excluded from church decorations, perhaps due to its lavacious folklore, or it’s strong pagan veneration, and in some places still is today. It is a good one to wrap up in red thread to protect the home from evil spirits. This use seemed readily adaptable to the Christian folklore as well.There are many traditions, but there are some beliefs that when you bring in the mistletoe on Christmas, you must keep it in for a full 12 months before removing it to keep away evil. The old mistletoe will then we burned when the new is brought in! Thus preventing evil spirits from entering for another year. There are many species of mistletoe, but for clarity’s sake, here we are speaking of the European variety. Many of the American species are more toxic, yet the European one, despite containing some toxic elements, has a long history in European folk medicine. It was even used as a Winter fodder crop for livestock. Dried mistletoe is widely available as an herbal tea in Europe, where the Phoradendron species so common in North America is absent. Pliny the Elder noted the Druid’s use of this plant harvested from their sacred Oaks for use in ritual and medicine. As I said before, Oak is not the most common tree this plant parasitizes, so finding it on those old giants would have been of special significance. The most common use of mistletoe as a tea is to address circulatory and blood pressure issues. The ever enigmatic founder of Biodynamic farming, amongst other things, Rudoloph Steiner, advocated mistletoe tea for cancer, and today there are many mistletoe based formula and clinics for treating cancer in Germany and Switzerland. I rarely use mistletoe internally since we don't have the appropriate species here in the U.S., but I do love to use pieces I find from windfall as talismans and protective amulets. I use it for luck in hunting and protection, especially from the unseen. Have a fine finish to your January and blessed Imbolc my darlins. Works Cited

Frazer, Sir James. The Golden Bough. Wordsworth Editions. 1993. Longmans Dictionary of the English Language, Penguin Book Ltd. 1991. Hole, Christina. A Dictionary of British Folk Customs. Helicon Publishing Ltd. 1995. Graves, Robert. The White Goddess. Faber and Faber. 1997. Encyclopedia of Superstitions, Folklore, and the Occult Sciences of the World. United States, University Press of the Pacific, 2003. Mac Coitir, Niall. Ireland's Wild Plants – Myths, Legends & Folklore. Ireland, Collins Press, 2010. Mushrooms have long been lauded as powerhouses of mystical healing properties. Today with writers and researchers like Paul Stametes and William Padilla-Brown and many more looking into the constituents and seemingly endless healing properties of fungi and lichens. Far from a new concept, the uses of mushrooms and lichens as medicines goes back to some of the earliest medicinal practices. Recently I met a mushrooms called Tinder Fungus, or Fomes fomentarius, and I am basically in love with it now. When I found this hard, shiny strange gray stripped polypore fungus on a hike near our home recently with my partner, I did not know the ID right away, but something in me said, grab one of these to ID, this is important. Upon our return home it took no time at all to learn its name. As we researched more about it, I was so excited to discover that it was one the fungi found on the ice mummy researchers have named Otzi the iceman. This gave the Tinder fungus its other common name, Ice Man fungus. It is also called hoof fungus and tinder conk for reasons we’ll see why. It is found in Europe, Asia, Africa and North America, this is a long lived mushroom. The fruit bodies are perennial, surviving for up to thirty years! The strongest growth period is between early summer and autumn. If you look at the mushroom sliced sideways, you can see how it grows in layers each year. It was used by our ancient ancestors to carry fire, giving it the name tinder fungus, and also to make a substance known as Amadou. The young fruit bodies are soaked in water before being cut into strips, and are then beaten and stretched which separates the fibers. The resulting material is referred to as "red amadou”, and I believe Paul Stametes wears a hat made of it! It was used in early medicine and dentistry due to its absorbent nature. Historically the tea of this mushroom was also a powerful medicine, which may explain why Otzi had it on him. He was found in the ice in the mountains between Austria and Italy, and lived between 3400 and 3100 BCE. I felt a strange feeling as I handled the fungus after that. Recently, my brother did an ancestry test and sent me the results, and interestingly enough, we were part of Otzi’s haplogroup. While that doesn’t mean we are direct ancestors of this famous mummy, it made me feel strangely connected, sitting there holding this fungus we found on a Beech tree here in North Carolina, knowing it was a tool, both for fire making and medicine, my Copper age ancestors may have cherished. He had it laced through a piece of leather, like a mushroom necklace or charm, which I love the idea of. It was most likely to ensure it was easier to carry, but it is beautiful. Tinder Fungus has been used as a tea for centuries in a wide variety of cultures. Though recorded as Agaricum in 200 AD, the fungus that was used to combat deadly diseases such as Tuberculosis in the Middle Ages is thought to be Fomes fomentarius or another close species, Fomitopsis Officina. Hippocrates in the fifth century BC described Fomes fomentarius as a ‘cauterization substance for wounds’. It would go on to be used in this way as amadou for centuries. This may be what gave rise to it’s other name: ‘surgeon’s agaric’. In European folk medicine, Fomes fomentarius was used to cure haemorrhoids, bladder disorders, and dysmenorrhea. I sliced the fresh fungus with a very sharp knife (it is hard to cut) and decocted (boiled it gently) for 30 minutes. It made a reddish, almost birch-beer like tea that I am now obsessed with. I drank a lot of it. I love it. The International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms has a lot of good things to say about the medicinal powers of the fomes. In their report "Anti-Infective Properties of the Melanin-Glucan Complex Obtained from Medicinal Tinder B. Mushroom, Fomes fomentarius (Aphyllophoromycetideae)", they say that Fomes fomentarius raises the immunity of the body, enhancing blood circulation, regulating blood sugar and lowering blood pressure. It also has shown its ability to fight the herpes virus, influenza and much more. From Trad Cotter: "These mushrooms are wonderfully rich in compounds similar to those of turkey tail (Trametes versicolor), including polysaccharide-K, a protein-bound polysaccharide commonly used in Chinese medicine for treating cancer patients during chemotherapy." I've added it to my turkey tail and reishi extractions for extra oomph. Fomes fomentarius is incorporated in the ancient Indian medicine as a diuretic. It is also used as a laxative to stimulate bowel movement. The fungus is also a remedy that steadies nerves. The Chinese used Fomes fomentarius in the treatment of cancer of the throat, the stomach and the uterus. The Okanagan-Colville peoples used the fungus to make antimicrobial teas and poultices to treat infections and arthritis. It was used to cauterize wounds by Laplanders and the Cree to treat frostbite. Excitingly, the mushrooms are also not just medicinal to humans, Paul Stametes found extract of the mushroom are great for bees, namely in reducing the number of deformed wing virus and Lake Sinai virus. Magically, it was used in smoking rituals in western Sibera and in Hokkaido it was believed burning the fruiting bodies overnight would banish evil spirits. The Khanty people, an indigenous population in what is known now as Russia, also used it ritual in a similar fashion but specifically was a funerary fungus. The smoke was produced through burning the fungus when a person died and it was continued until the deceased person had been taken out of the house. The people coming from the funeral also had to pass through smoke. The aim of the procedure was not to let the dead have any influence on the living. I do so love it when a plant or mushroom is good for immunity or disease and it also has a corresponding metaphysical purpose as a clearer of evil or spirits. As above. So below. As in all things, over-harvest can be a problem. These are long lived, slow growing mushrooms. Please NEVER harvest lots of or make medicine with a mushroom you are unsure of ID for. Taking just a few and making a double extraction of the medicine is a much better way to make use of rarer fungi, as using the tea or powders only, despite being traditional, does use more matter. This great blog post goes into some detail and lists further resources on growing these amazing beings. Wait, wait. What is a double extraction? All this great info about mushrooms made me realize, I’d like to give you the quick and dirty on making medicinal mushroom double extractions. You can do it with your new friend the tinder fungus, or turkey tails, reishi, chaga, shitake, lion’s mane, Usnea lichen and so many more. Obviously there are 100 ways to do things in herbalism and medicine making, so I will give the very basic outline and theory behind it, and tell you what I do. There are many much more knowledgeable medicine makers older and wise then I. +Making a Mushroom Double Extraction+ Mushrooms contain a lot of different types of constituents. Some are easily water-soluble (polysaccharides) and some are less soluble (terpenoids and phenolics). By doing the double-extraction process, it allows you to utilize the full spectrum of constituents in one medicine. The simple steps are:

If you want to forgo measuring and make a folk tincture (i.e. one that is eye-balled and not necessarily exact but still kickass), just make sure to tincture the mushrooms or lichen in 80 proof or higher alcohol and ad one part water extract to one part tincture. That should leave you at roughly 25-35% alcohol and be shelf stable. Pro tip: If tincturing feels confusing, (I’m terrible at math and it made me feel mad at first), check out 7song’s very helpful PDF on tincturing to make it clearer. Now go be free, drink mushrooms, feel like a Copper Age human and wear Tinder fungus as jewelry! Well, you don’t have to do any of that, but I hope this toe into the world of mushroom medicine has at least tickled your fancy. If you want to get wild and actually DO this with me and Abby Artemisia, check out our Folk Herbalism and Wild Food Foraging school, The Sassafras School of Appalachian Plantcraft. We have two more days to get the Early bird discount! Blessings in the New Year (even though the seasons are a wheel and have no beginning or end)! +Works Cited+

http://www.medicalmushrooms.net/fomes-fomentarius/ https://permaculturenews.org/2016/08/22/fomes-fomentarius-french-alps-paul-stamets/ Buhner, S.H. (2012). Herbal Antibiotics. North Adams, MA: Storey Publishing. Rogers, R. 2011. Fungal Pharmacy. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books Saar, Maret. “Fungi in Khanty Folk Medicine.” Journal of Ethnopharmacology, vol. 31, no. 2, 1991, pp. 175–179., doi:10.1016/0378-8741(91)90003-v. Stamets, P. 2002. MycoMedicinals An informal treatise on mushrooms. Hong Kong: Colorcraft Ltd. There are many names for the transition between October and November. The Celts called it Samhain, which means ‘Summer’s End’ and it is the last of the three harvests that began at Lammastide. It was now that animals were killed and meats preserved for winter use to ensure the clan's survival. It was, and is, the festival of the Dead. Dumb Suppers were silently eaten with the beloved departed, while divination was fruitful on this spirit night when the veil between the Dead and Living thinned. The Wild Hunt rides in chaos over the land and the dead roam freely, can't you hear them today on the wind? We light bonfires to drive away darkness and prayers said for the dead. The Hidden Company draws near and some cast two circles, one for the living and one for the dead during their rites. Halloween, with May Eve and Midsummer's Eve, is one of the three 'spirit nights' of the year when the veil between the worlds is thin, allowing for this unearthly conference. The Dark of the year that we sit in now is a time for planning, rest and contemplation. It ends at the Yuletide when the Old Woman and the Horned One begin the year anew. Look into the shadows now, without fear and learn from the Dark Ones. Do not fear the Dark. In Wales it was called calan gaef or the 'first day of winter', while Halloween was nos calan gaef or 'winter's night'. Despite the Wiccan persistence in treating Samhain as the Celtic New Year, there is little evidence to support this idea. In fact this idea is more likely to have developed in the romanticization of the Celts that happened in the late 19th century. To the Anglo-Saxons, early November was the time when surplus cattle, sheep, and pigs were slaughtered and the meat salted to see the tribe through the winter months. Writing in the 8th century the Venerable Bede said that the pagan Saxons called November Blodmonath or blood month. In a religious sense, it was when the blot was performed, the pre-winter sacrifice of animals to the Gods in the hope that the weather would not be bad and not too many of the clans group would die before Spring of Winter illnesses. To our Celtic, Saxon and Norse ancestors Samhain was a festival for the dead. It was a special time when summer gave way to winter and supernatural forces were believed to be on the loose. The early Christian Church decided to move the Festival of All Saints from May 13 to November 1 in 835 CE. A century later, November 2 was declared All Souls Day when it was the Christian custom to pray for the souls of the dead in Limbo. These Church festivals may have influenced the folk customs of All Saint's Eve or Halloween, however, it is more probable that much of the older pagan customs were remembered in these folk customs. Sometimes the Church preserved the very things that it attempted to stamp out. +The Apple+ The apple was considered a symbol of immortality. Interestingly, it's also seen as a food for the dead, which is why Samhain is sometimes referred to as the Feast of Apples. In Celtic myth, an apple branch bearing grown fruit, flowers, and unopened buds was a magical key to the land of the Underworld. Allantide apples. Peel the apple, keeping the peel in one long piece. When the peel comes off, drop it on the floor. The letter it forms is the first initial of your true love's name. Wait until midnight and cut an apple into nine pieces. Take the pieces into a dark room with a mirror (either hanging on the wall or a hand-held one will do). At midnight, begin eating the pieces of apple while looking into the mirror. When you get to the ninth piece, throw it over your shoulder. The face of your lover should appear in the mirror. The completion of the fall harvest was considered to be the start of the winter season by many early cultures, even though they were well aware of the motions of the sun, including the winter solstice, by which we in modern times mark the beginning of winter. In the Celtic dialect spoken in Cornwall, this annual autumn celebration was known as Kalan Gwav, which translates as first day of winter. At some point after Christianity came to Britain, Kalan Gwav melded with the All Hallows’ observances. But as the use of the Cornish language diminished, this celebration came to be associated with an obscure Cornish saint, St. Allan, and was known in English as Allantide, "tide" being an arcane suffix meaning a season or a period of time. Since apples were strongly associated with love and marriage, it was believed they had the power to reveal their prospective spouse to those who had not yet married. Young Cornish men and women approaching marriageable age would often sleep with the "Allan" apple they had been given under their pillow, or under their bed, on the night of the day they received their apple. They did so in the hope of dreaming of their future wife or husband. In some districts, it was believed that this dream of future love would only come true if the dreamer ate their apple on the following day. The other divination game which involved suspended apples had become popular in the area of Penzance around the turn of the nineteenth century. It was still played there during the Regency at Allantide. Two strips of wood, each between eighteen to twenty inches long and about an inch to an inch and a half wide, were nailed together to form a simple cross. Four candles were placed on the top of each arm of the cross. This candle-laden wooden cross was suspended from the ceiling, usually in the kitchen of the home. Then, an Allan apple was hung by a short string from each arm of the cross. In many households, as with bobbing apples, marriageable maidens would have placed their mark on one of the apples before it was suspended from the cross. When it came time to play the game, the candles were lit and the boys gathered beneath this Allantide "chandelier." Each boy took turns jumping up to try to catch an apple in his mouth. Boys who were too slow or missed the apple and hit one of the arms of the cross were likely to get a blob of hot wax in the face for their efforts. +The Last Sheaf of Grain+ The last sheaf of rye is left to the Roggenwulf, or Rye wolf, during the winter’s cold. In Germany when wind blows the tall gass or corn the “Grass wolf” or “Corn wolf” is among the blades. Many final harvest ceremonies involved the final harvest of grain: “Crying the Neck” in England and Wales: "In those days the whole of the reaping had to be done either with the hook or scythe. The harvest, in consequence, often lasted for many weeks. When the time came to cut the last handful of standing corn, one of the reapers would lift up the bunch high above his head and call out in a loud voice....., "I 'ave 'un! I 'ave 'un! I 'ave 'un!" The rest would then shout, "What 'ave 'ee? What 'ave 'ee? What 'ave 'ee?" and the reply would be: "A neck! A neck! A neck!" Everyone then joined in shouting: "Hurrah! Hurrah for the neck! Hurrah for Mr. So-and-So” (calling the farmer by name.)" +Hazelnuts and Chestnuts+ This is an old Scots and Northern English name for Halloween, the night of 31 October, otherwise called The Oracle of the Nuts. As the chill of autumn pervaded their homes, people would sit around their fires, eating newly harvested hazelnuts or chestnuts. Several fortune-telling customs grew up that involved throwing nuts into the fire, hence these names for the night. A young man might give each nut the name of a possible sweetheart and watch to see which burned the brightest in the flames. This is evoked in John Gay’s poem, The Spell: Two hazel-nuts I threw into the flame, And to each nut I gave a sweetheart’s name: This with the loudest bounce me sore amazed, That in a flame of brightest colour blazed; As blazed the nut, so may thy passion grow, For ’twas thy nut that did so brightly glow! Robert Burns recorded several related customs about this day, one of which was a fortune-telling game for a young couple in which two nuts were put in the fire. Their future was predicted depending on whether the nuts burned quietly together or jumped apart. An elaborated description appeared in an American publication of 1912, Games for Hallow-e’en, by Mary E. Blain: “A maid and youth each places a chestnut to roast on the fire, side by side. If one hisses and steams, it indicates a fretful temper in the owner of the chestnut; if both chestnuts equally misbehave it augurs strife. If one or both pop away, it means separation; but if both burn to ashes tranquilly side by side, a long life of undisturbed happiness will be their lot.” Filberts are the European variety of hazelnuts, and in some parts of England, they were used for divination purposes around Samhain night. In fact, for a while the practice was so popular that Halloween was sometimes referred to as Nut Crack Night. Filberts were placed in a pan over a fire and roasted. As they heated up, they would pop open. Young women watched the filberts carefully, because it was believed that if they popped enough to jump out of the pan, romantic success was guaranteed. In some areas of Europe, the nuts were not roasted, but instead were ground into flour, which was then baked into special cakes and dessert breads. These were eaten before bed, and were said to give the sleeper some very prophetic dreams. In a few regions, the flour was blended with butter and sugar to create Soul Cakes for All Soul's Night. If a young lady peels an apple without breaking the peel; then throws it over her back; it will land in the shape of the initial of the person she will marry? This old wives tale originated in the British Isles-where it was supposed to be performed on Halloween. The traditions of trick or treating and dressing up in costumes also came from the British Isles. However you celebrate Samhain, remember that the land you live on is alive with Spirits all the time, not just tonight. Ask them what they want, just as we ask each other what we need to feel fulfilled in relationship, and feed the Hungry Ghosts. +Further Reading+

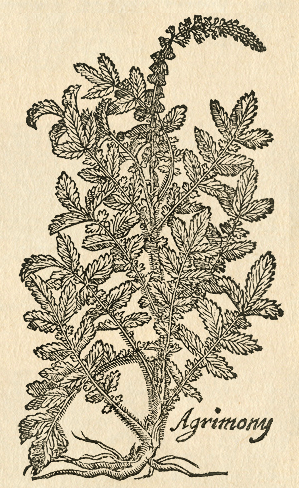

Rogers, Nicholas. Halloween : From Pagan Ritual to Party Night. Oxford University Press, 2002. Midsummer has passed, the Full moon in July is complete, and Lammas is here. The first Harvest is upon us. I always feel that time is either going too fast or too slow, very infrequently does it seem to be just right. But maybe it is just right, and I just need to learn to slow down. The once tame garden is now wild with flowers and squash and kale and peppers and so so many wild greens. Every day we make meals of Leatherback mushrooms fresh foraged from the dark woods with tender yellow squash and pungent, freshly harvested garlic. Grass fed beef from the farm behind ours and sheep’s milk yoghurt from another neighbor. Curly and bitter dock seeds are harvested to grind for flat bread, and the ubiquitous violets, magenta lambsquarters, ox eye daisies and nettles fill our bowls. It’s hot, we sweat, we swim, we struggle, and we laugh. We’re almost through the Dog Days of Summer. That special time when Sirius, the Dog Star, is overhead and in Appalachian folklore, dogs and snakes are more likely to bite, tempers flare and wounds are slow to heal between July 3rd and August 11th. This term stems all the way from ancient Romans, who believed the bright light of the Dog Star actually added warmth of its own to the sweltering Summer heat. In fact it doesn’t, but the term has traveled through the ages and settled into the languaging of here, the place where I dwell. So many plants are blooming or getting ready to, and I’m excited to spot some small yellow flowers soon. The flowering tops of one of the most humble members of the Rosacaea family: Agrimony. The name alone reminds me of my childish fascination (and let’s be real it obviously never ended) with all things witch-related. It just sounds spooky perhaps, or like the word itself is a spell, a word of power. The word Agrimony comes from the Greek agremon which was believed to refer to cataracts in the eyes. There is some confusion about the origin of the word, however, for it may have been referring to a type of Poppy. However its name came about, I love this plant which I rarely see mentioned. There are many species of agrimonia, 15 in fact, but only about four boast a reputation as healers. Agrimonia eupatoria, which is native to Europe, North Africa, Southwest Asia, and Macaronesia, is an introduced species in North America. Agrimonia pilosa is native to Asia and Eastern Europe and Agrimonia gryposepala and parviflora are native to North America. Like many other Rosaceae family members, the tannins in this plant are one of the sources of its powers. Tannins are are a class of astringent, polyphenolic biomolecules, (I know it’s a mouthful), that bind to and precipitate proteins and various other organic compounds including amino acids and alkaloids. This is why, it makes your mouth pucker and feel dry when you drink tannic tea; it binds to the proteins present on the mucus membranes of the mouth. This tightening of the flesh is what causes tannin rich plants to be so useful medicinally as wound washes, for inflammation and bleeding. Historically, starting in ancient Greece, Dioscorides mentions the seeds and herb infused in wine being useful for dysentary, and the leaf for hard to heal ulcers, speaking to its tannic nature. It was also indicated as a liver herb, or for “faults of the liver”. The Anglo Saxons called it “garclive”, and used it for snake bites according to Madame Grieve, who woefully often does not cite her sources. She does give this charm though, “If it be leyd under mann’s heed, He shal sleepyn as he were deed; He shal never drede ne wakyn Till fro under his heed it be takyn’ (Grieve, 1931, p. 13)”. Other Medieval herbalists used it similarly, and this line, between waking and sleeping, awareness and lack thereof, seems to be the domain of this humble plant. From Hildegard von Bingen’s Physica: “Let a person who has lost understanding and knowledge have the hair cut from his or her head since the hair creates a horrible and shaking tremor. Then cook agrimony in water and wash the person’s head with this warm water. Also, the herb should be tied warm over the heart when the person first senses mindlessness. Then place it warm over the forehead and temples. The person’s understanding and knowledge will be purified, and the mindlessness will leave.” She also recommends it for, “bile and mucus from intestines (wine infusion), saliva, excretions, and runny nose (in complex formula, pill form), leprous skin condition due to incontinence or lust (complex formula, bath), and cloudy eyes (pounded agrimony placed around the eyes at night with a cloth, not entering the eyes).” Its vulnerary uses persisted in Europe, and mixed with vinegar and Mugwort, it was applied to a variety of wounds. Its powers to stop bleeding were apparently made more powerful by the recommendation of adding pounded frogs and human blood to treat internal hemorrhaging. In England in the 18th century, the juice and crushed leaves were still being used commonly for injuries and wounds by common people. In Ireland, this plant was sometimes known as Marbhdhraighean in Gaelic. It was also sometimes known as “tea-plant”, which as you can guess, was due to its use as a substitute for tea during lean times. There, it was used for colds, liver issues and as well as old ulcers. The species of the Americas, a. gryposepala or parviflora, were used by native peoples and here where I live, in Cherokee it is called a la s ga lo gi. They use it as a tonic and blood purifier. The Cherokee also used infusions for similar issues of bleeding, urinary issues and more—often of the root, which was not commonly used in Europe. They were used for skin issues and pox, as a gynecological aid, for fevers, and many other ailments. Today, Agrimony is used for urinary issues, gastro issues, respiratory problems where breath is limited and wounds. Things haven’t changed too much, but we just won’t add frogs to our mix. Of course it also has other uses. Agrimony is also a lovely dye plant and yields a yellow dye, much likes its small joyous flowers. When braided together with Rue, Maidenhair Fern, Broom, Ground Ivy, it was believed in Tyrol to reveal the presence of witches, and held them fast on the threshold. We see many stories of the power that different plants have to reveal witches beneath thresholds. How one enters or exits a place does indeed say a lot about them doesn’t it? According to Culpeper, Agrimony is attributed to Jupiter and Air. In Hoodoo, Agrimony has the unique ability to turn back jinxes that have already been made. This is interesting because most herbs are focused on preventing a working. It is also said to represent gratitude. What a good reminder at any time of year. One of its old names, Church Steeples, is evident this time of year as the tall flower spikes of yellow flowers stand upright, waving in the hot, late Summer breezes. The association of the holy place, a church, with this plant further exemplifies its uses against evil and as a jinx breaker. While you walk the cool forest trails as Summer’s end comes into sight, please give a nod to this sweet little plant and feel its soft fuzz between your fingers. Hail Summer’s End, and the beckoning Dark times ahead. Works Cited:

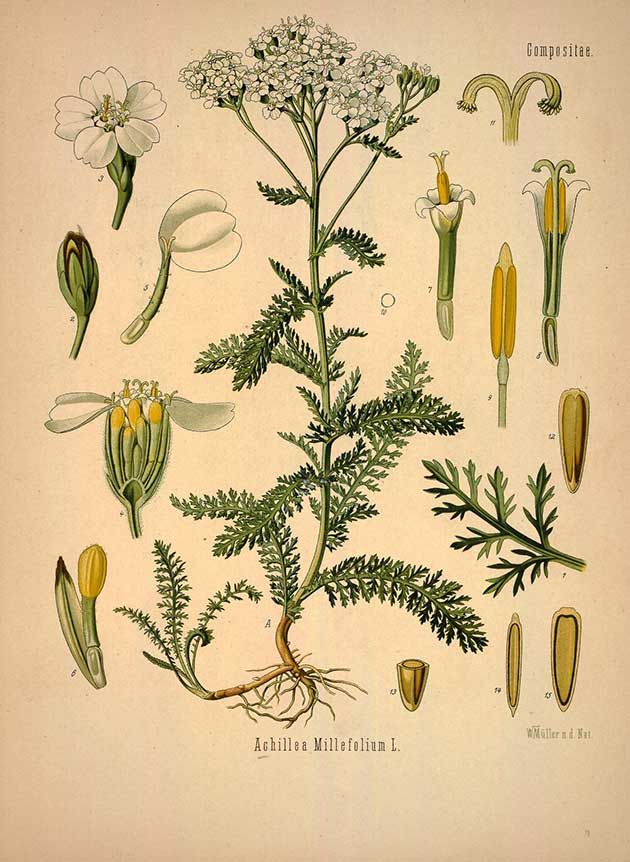

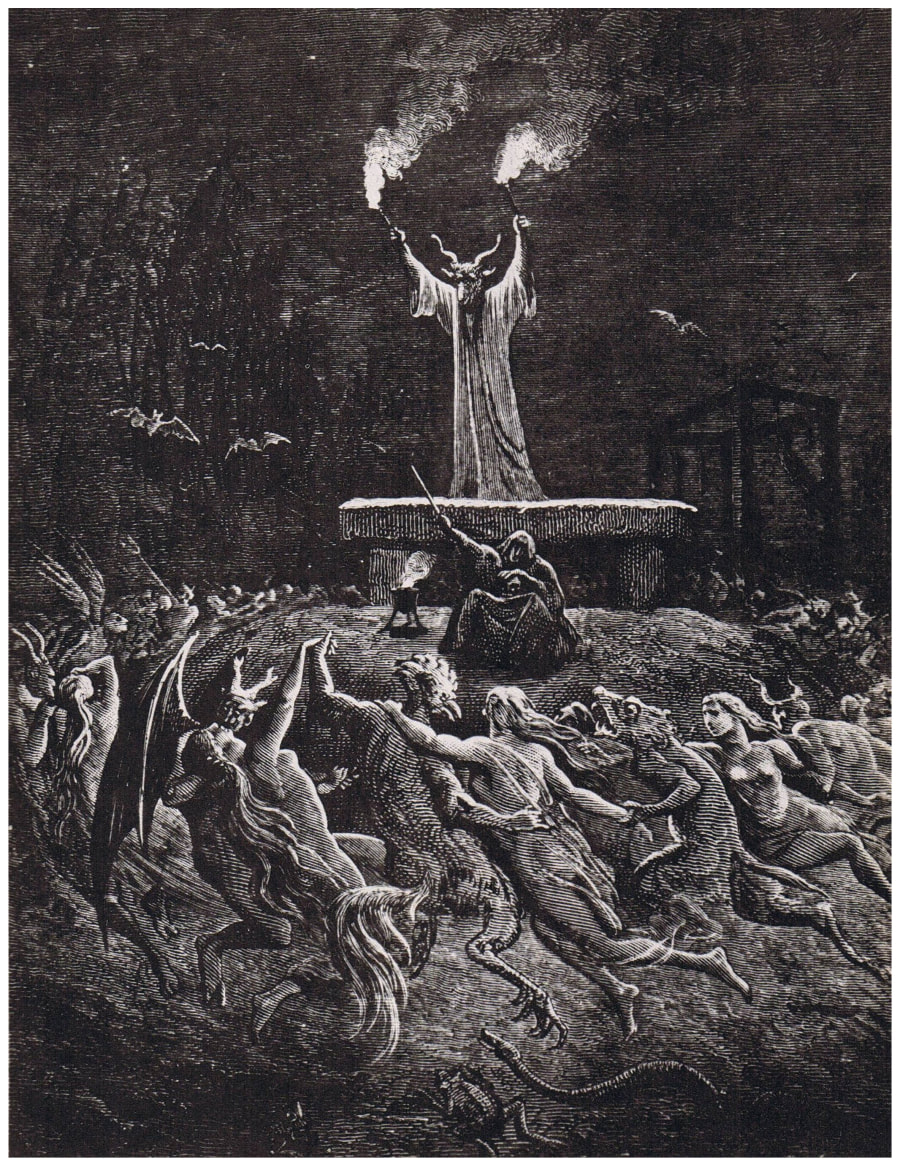

Allen, D., Hatfield, G. Medicinal plants in folk tradition. An ethnobotany of Britain & Ireland. Portland/Cambridge: Timber Press. 2004. Culpeper, N. Culpeper’s complete herbal. London: W. Foulsham & Co., Ltd. 1880. Garrett, J.T. The Cherokee herbal. Native plant medicine from the four directions. Rochester, VT: Bear & Co. 2003. von Bingen, H. Hildegard’s healing plants. From her medieval classic physica. Trans. Bruce W. Hozeski. Boston: Beacon Press. 2001. Watts, Donald. Dictionary of Plant Lore. Academic, 2007. Wood, M. The earthwise herbal. A complete guide to old world medicinal plants. Vol. 1. Berkeley: North Atlantic Herbs. 2008. It is almost Midsummer. We face opposite the depths of Winter, at the highest point of the Sun’s journey. Sometime between June 20th and the 23rd, Midsummer’s Eve, the Wild Hunt, spectral hunting party of the Horned God/dess of Many Names rides out.They gather the lost souls of the dead who wander the Earth, to return them to their rightful realm. Summer thunderstorms brew in the distance and the air feels electric. This, Samhain and May Eve are the three ‘spirit nights’, when the veil is the thinnest. This is one of the liminal times. It was believed that contact could be made with the Good Folk at the 'tween times of dusk on Midsummer's Eve and dawn on Midsummer's Day. Liminal spaces ‘twixt the boundaries of here and there are all historical places to meet the Fae. Beneath certain trees, springs, special earthen mounds, places that are between states. These places are also the meeting houses of Witches, as is expected. Midsummer’s Eve is especially fine for divination, and there is a long and rich history of divining for one’s true love this night. This is a ghostly time, though the Sun is warm and the days are long, every day now until Winter Solstice, becomes shorter and shorter, asking us to face our own mortality and that of the good Earthly beings around us. The shadow of the Reaper’s scythe is cast over the verdant fields. Many herbs have long standing traditions of use as charms and medicines around this time of year, plants like Mugwort, St. Johnswort, and many more. One of my favorite plants of this season is Yarrow, Achillea millefolium. The white clusters of Yarrow are blooming around the mountains now, preparing us for the upcoming eve of June 20th, and the dawn of Midsummer’s Day, June 21st. I gather the blooms and leaves on Midsummer’s Day when the Sun is at its zenith point, drawing upon that peaked energy for empowerment of charms, talismans and medicines. Yarrow has a long history of use from ancient Greece and Rome, where it earned its latin name, Achillea from the legends of Achilles. In Greek mythology, Thetis bathed Achilles in Yarrow, which gave the hero, Achilles, its protective powers to make him invincible wherever the liquid had touched his skin, save for his heel, which was never submerged. Achilles also healed his wounded soldiers with Yarrow, a great styptic herb, the warrior’s herb. Scotland has a large repository of lore surrounding Yarrow as well. An interesting Gaelic woman's incantation from the Carmina Gadelica that is spoken when picking Yarrow goes: "I will pick the smooth Yarrow that my figure may be sweeter, that my lips may be warmer, that my voice may be gladder. May my voice be like a sunbeam; may my lips be like the juice of the strawberry. May I be an island in the sea; may I be a star in the dark time, may I be a staff to the weak one. I shall wound every man, and no man shall hurt me." It is disputed as to whether this plant repels or draws faeries, and I implore you to see what you think. Yarrow is associated with the element of Air, as it is aromatic. It is also useful in divination, combine it with Mugwort and Chamomile as a tea and dream of things to come. Historically, it was used for divining one's future lover or determining whether one is truly loved. In Appalachia it was stuffed up the nose to divine if one’s true love reciprocated the sentiment: “ Green yarrow, green yarrow, you bears white blow, If my love loves me my nose will bleed now.” It was also used in love sachets, because it is believed to be capable of keeping a couple together for 7 years. It was also used protectively, much like mugwort. It was strewn across the threshold to keep out evil and worn in charms to protect against hexes. It was also tied to child’s cradle to protect it from those who might try to steal its soul. The Saxons wore amulets made of this plant to protect against blindness, robbers, and dogs. For a love charm: “Yarrow, sweet Yarrow, the first I have found. In the name of the Lord, I pluck thee from the ground. As the Lord loves the Lady, so warm and dear, So in my dream may my lover appear.” However you use Yarrow in your rites, remember that for good or for ill, Yarrow is of the deep, red blood of the heart. The Warrior's herb, the Lover's herb, the Healer. Works Cited: The Carmina Gadelica The Celtic Magazine, Volume 9, p.431. Edited by Alexander Mackenzie, Alexander Macgregor, Alexander Macbain. Walpurgisnacht approaches April 30th. Celebrating the holidays of my ancestors has provided a lot of healing for me. Sinking into a space, though not entirely perfect, authentic or completely unbroken in its lineage, of ancestral lifeway is one of the many tactics I see for helping to heal the emptiness that can inhabit whiteness. Where a cultural void lives, things will come to fill it, and we can become much more apt to cause harm to minority and oppressed cultures as we seek to fill that painful void. As you may know from my other work, I am passionate about facing cultural appropriation, and while things are complex, nuanced and there is no one-size-fits-all solution for any problem, nor do I hold any real “truth” or “authority”, this is how I am choosing to deal with the ways in which oppression has erased my own access to a cultural legacy… I am looking into the pre-Christian past of my ancestors, and allowing the Old Ways to meld back into my current Lifeway. One of those Ways, is observing the Old Holy Days. The lesser celebrated holidays are often the most special to me, perhaps because they have retained more of their original meat. I’ve enjoyed celebrating this special night and watching the strange parallels during this markedly un-spooky time as we stand across from Samhain, All Hallows… The ways in which the eve of April 30th and October 31- Nov 2nd are rife with omens, the frightening of spirits and divinations is uncanny, and delightful I must say. I hope this brief foray into the lore of this special night will tantalize you... This forgotten Germanic holiday is defined by Sturm and Drang or “Storm and stress”. They say March is, “in like a lion, out like a lamb,” and this is reflected in the energetic flavor of this season. Both Celts and Germans valued what we know now as Beltane, their cultures often overlapped in sacred observances. They both observed this night before May Day with bonfires in which they burned Fennel, Rue, Chevril, Thyme, Chamomile, Pennyroyal, and Geranium for Celts, and Rosemary, Juniper, Rue, Hemlock, Blackthorn, and Wild Caper for Germans. Goethe used the wild night as a backdrop for Faust, revealing this obscure night to a much broader audience, thus reigniting an interest in this wicked holiday. This night, as often is the case, is named after the St. Walpurga, an 8th-century abbess of Francia, and is celebrated on the night of 30 April and the day of 1 May. This night celebrated the canonization of Saint Walpurga and the movement of her relics to Eichstätt, both of which was said to have occurred on 1 May 870. Saint Walpurga was hailed by the Christians of Germany for battling "pest, rabies and whooping cough, as well as against witchcraft." In Germanic folklore, Hexennacht, literally "Witches' Night", was believed to be the night of a witches' meeting on the Brocken, the highest peak in the Harz Mountains, a range of woodland in central Germany. As is often the story, this saints day superseded the festivities of May Day and supplanted the Old Pagan celebrations. However, call it what you may, they cannot erase the Old Ways entirely, no matter how hard they try. In eastern Europe, pitchforks of burning hay were waved about this eve to impart the power if the sun to the fields in an act of imitative magic. As in many Scandinavian traditions, people made noise with loud gun firing and noisemaking to drive out evil. In medieval Europe, the night of April 30th represented Queen May’s 11th hour bid to take back forest and field from king winter before he was driven off, one can see a reflection of this more modern pagan mythology in the Pagan stories of the Oak and Holly king. At this time, protection bundles of Elder leaves hungover animals stalls and wild roses in Bohemia and in North Europe crosses of Hawthorne, Rowan, Birch crosses were nailed to lintels of house and barns. Essentially, this Germanic Walpurgisnacht celebration resembles Celtic Beltane. In other European countries, sprigs of Ash, Hawthorn, Juniper, and Elder, once sacred to the Old gods, are now used as a protection against them. Horseshoes are nailed prongs up on the threshold or over the door. Holy bells are hung on the cows to scare away the witches, and they are guided to pasture by a goad which has been blessed. Shots are fired over the cornfields to frighten away ill spirits. If one wishes, they can hide in the corn and hear what will happen for a year. It is also a night to look for signs and omens, for on Walpurgis Night, they have more weight that at other times of the year save for on St. John's Day, or Midsummer. There are many lovers omens on this eve, just like in Scotland on All Hallows. They say if you sleep with one stocking on, you will find on May morning in the toe a hair the color of your sweetheart's. Girls try to find out the temperament of their husbands-to-be by keeping a linen thread for three days near an image of the Madonna, and at midnight on May Eve pulling it apart, saying: "Thread, I pull thee; Walpurga, I pray thee, That thou show to me What my husband's like to be." They judge of his disposition by the thread's being strong or easily broken, soft or tightly woven. Dew on the morning of May first makes girls who wash in it beautiful. "The fair maid who on the first of May Goes to the fields at break of day And washes in dew from the hawthorn tree Will ever after handsome be." A heavy dew on this morning presages a good "butter-year." You will find fateful initials printed in dew on a handkerchief that has been left out all the night of April 30th. On May Day girls invoke the cuckoo: "Cuckoo! cuckoo! on the bough, Tell me truly, tell me how Many years there will be Till a husband comes to me." Then they count the calls of the cuckoo until he pauses again. If a person wears clothes made of yarn spun on Walpurgis Night to the May-shooting, they will always hit the bull's-eye, for the Devil gives away to those he favors, "freikugeln," bullets which always hit the mark. On Walpurgis Night it is a spooky time, similar to the flavor of Halloweentide. From the Book of Hallowe'en: Zschokke tells a story of a Walpurgis Night dream that is more a vision than a dream. Led to be unfaithful to his wife, a man murders the husband of a former sweetheart; to escape capture he fires a haystack, from which a whole village is kindled. In his flight he enters an empty carriage, and drives away madly, crushing the owner under the wheels. He finds that the dead man is his own brother. Faced by the person whom he believes to be the Devil, responsible for his misfortunes, the wretched man is ready to worship him if he will protect him. He finds that the seeming Devil is in reality his guardian-angel who sent him this dream that he might learn the depths of wickedness lying unfathomed in his heart, waiting an opportunity to burst out. Both May Eve and St. John's Eve are times of freedom and unrestraint. People are filled with a sort of madness which makes them unaccountable for their deeds. "For you see, pastor, within every one of us a spark of paganism is glowing. It has out-lasted the thousand years since the old Teutonic times. Once a year is flames up high, and we call it St. John's Fire. Once a year comes Free-night. Yes, truly, Free-night. Then the witches, laughing scornfully, ride to Blocksberg, upon the mountain-top, on their broomsticks, the same broomsticks with which at other times their witchcraft is whipped out of them,--then the whole wild company skims along the forest way,--and then the wild desires awaken in our hearts which life has not fulfilled." --SUDERMANN: St. John's Fire. Stay tuned for an Herblore of Walpurgisnacht e-book in the works... and have a wonderous and windy Walpurgisnacht... Works Cited:

The Book of Hallowe'en By Ruth Edna Kelley Night of the Witches by Linda Raedisch. 2017. The Equniox is right around the corner and I've got eggs on my mind. Two week ago, my hens started laying again, perfect brown eggs. They fill me with such delight. We have them in a chicken tractor and they run about, lie on their sides in the sun like little pancakes and chase each other and unseen bugs and things all day. The nourishment they are able to create our of the bugs and grass, plus compost treats and grain we give them, is astounding. They are truly alchemists. It's almost time to celebrate the burgeoning growing year and bid hello to the wild flowers of Appalachian Spring time. I figured it as good a time as any to talk about Egg magic. Eggs are used in many traditions for charming, hexing and curing. The Anglo- Saxons and Egyptians both placed eggs in their grave goods as well as on physical grave sites. There is no other symbol of new life so universal and apparent as the egg. Lying in wait to birth whatever being, or magical intention they hold. The tradition of egg dyeing that is quite popular in Easter customs today, most likely comes from Eastern Europe where the arts of Pysanky and Krashanka (two forms of decorated eggs) were born.

A red- dyed Krashanka bound with wheat and hung in a new house soothed disturbed spirits and invited spirit protection. The shells are dyed many colors to correspond to their uses. Red dyed eggs were thrown into rivers to alert those in the Otherworlds that Spring had come and the Season of the Sun had returned. These were also placed on the graves of loved ones and check the following day for any disturbance. If any was detected, it was made known that their restless spirit was in need of a prayer, offerings or other releasing rituals. Eggs were also placed under beehives to keep bees from leaving and to ensure good honey crops. When rolled in green oats, the dyed eggs acted as fertility charms when buried in fields as well. You can also write upon an egg any spell or wish you have an bury it in some secret place. As it decays, so does your wish disseminate into the ether. I'm preparing for Spring by starting seeds and looking to the signs. Some in East Anglia would see if the time was right for planting by removing their trousers and sitting upon the land to feel its warmth. I have laid my own bare bottom on the Earth many times, but never with such a practical purpose! As the sun warms the soil, if possible, get your skin in contact with the soil. Why wouldn’t you want to take off your pants outside!? It sounds like a great time to me. Still others would walk their land and ‘feel it in their bones’ as to whether or not it was the right time to plant. The lighting of bonfires in or adjacent to planting places with much singing and leaping dances would show the crops to grow tall and strong while the roaring fire would entice the sun to lend its life giving flames. The old beliefs about planting with the waxing moon and weeding with the waning further enliven the process of seed sowing with magic as the moon’s growth stimulates that of the seeds. “As above, so below.” The practice of planting by that signs carried over strongly with German immigrants to the Appalachians, where it surely mixed with First Nations and African beliefs from enslaved peoples, it has become the complex and rich story of living by the signs we have in the mountains today. Planting By the Moon and Signs Planting by the signs is an ancient practice going back thousands of years. This form of agricultural astrology is used in biodynamic and old forms of Appalachian farming techniques. The gravitational pull off the moon and planets is said to influence groundwater and its movement through plant bodies. Sometimes the lines between science and magic are blurred. If you'd like to join me in a journey to learn the ins and outs of planting by the signs, I'll be holding a class on it in Barnardsville, NC April 20th. Check it out and may your Rites of Spring bring you joy and may your seeds sown bear fruit. Works Cited:

Wheel of the Year: Living the Magical Life by Dan Campanelli and Pauline Campanelli The Pattern Under the Plough by George Ewart Evans |

Archives

April 2024