|

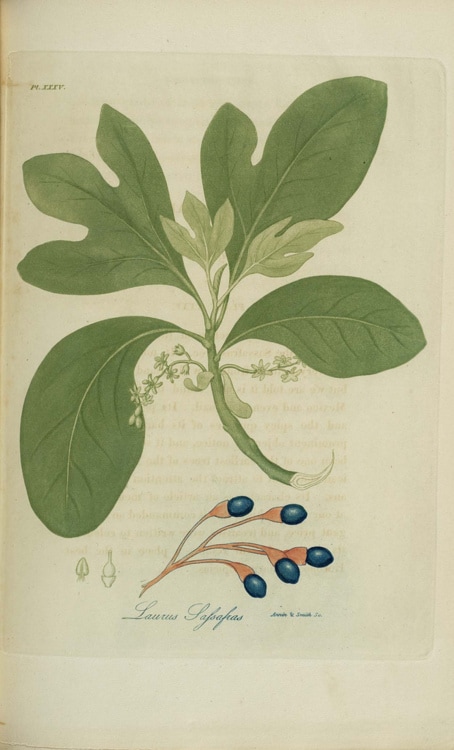

The early Spring of the year is past and early Summer it seems, has taken hold. This brings up thoughts of Spring tonics and other Spring practices. Cleaning, fixing, and starting anew. Though I want to focus on the uses of the wood of this lovely native, shrubby tree, I also want to wade through it's amazing uses in all the other realms it occupies. So let's meet Sassafras albidum, Sassafras, Winauk, cinnamon wood, ague tree, sassafrax, or saloop. This native tree is rife with folklore, medicinal and culinary uses. I love it, and I have to say, though some accuse me of saying this of every plant I meet, it is truly one of my most favorites. Sassafras is a native memeber of the Lauraceae family, and is one of three extant species. Early European colonists in America noted that the plant was called winauk by Native Americans in Delaware and Virginia and pauane by the Timucua. Native Americans distinguished between white sassafras and red sassafras, which to be clear refers to the same plant but to different parts with distinct colors and uses(1). Sassafras albidum is a fairly common "weed tree" which ranges from southern Maine and southern Ontario west to Iowa, and south to central Florida and eastern Texas, in North America. It is also a key ingredient in Appalachian Spring tonics. In Appalachian folk medicine, you can think of blood like the sap of a person. It rises in Spring and falls in Winter. It can be augmented and moved by taking certain herbs and tonics. A tonic being an herbal preparation that is used for the maintenance of health rather than the acute treatment of symptoms of a disease. That's how I think of it. To move the slow blood of Winter in Spring, there were many traditional plant medicines taken and prepared in the mountains. Some of the tastiest are sassafras, spicebush, cherry bark, and black or sweet birch. Bitter herbs also make up the other class of Spring tonics. Dandelion, burdock, dock, poke, wild onion, ramp, strong tea of red clover blossoms, yellow root, and nettles all share mineral rich or liver support properties. Or, well, they are at least very pungent. Sassafras is often easily identified by its unique leaf shapes, for it has what is botanically known as heterophylly, or multiple leaf shapes on one plant. It has the single lobe, the two lobbed “mitten”, and the three lobbed “dinosaur” foot as I likes to call it. I have even recently found a 5 lobed sassafras on Mill Ridge in WNC. It was used by First Nations folks in our bioregion and eventually passed into settler use as well. It was touted as a blood cleanser and included in recipes for the Spring tonics with plants like spicebush (Lindera benzoin), mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum), goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis) and other fragrant or bitter herbs. The modern herbalist Stephen Harrod Buhner (Sacred and Herbal Healing Beers, Brewers Publications, 1998) says: "Sassafras was the original herb used in all “root” beers. They were all originally alcoholic, and along with a few other medicinal beers — primarily spruce beers — were considered “diet” drinks, that is, beers with medicinal actions intended for digestion, blood tonic action and antiscorbutic properties. The original “root” beers contained sassafras, wintergreen flavorings (usually from birch sap), and cloves or oil of cloves. Though Rafinesque notes [in 1829] the use of leaves and buds, the root bark is usually used, both traditionally and in contemporary herbal practice." In Appalachia, its uses were first shared with Spanish and Europeans settlers. It had a myriad of uses to the Cherokee as a tea. The Cherokee even used it for weight reduction, which passed into use by European settlers and is still present today in the folk lexicon. Sassafras was one of the first plants exported to Europe from the New World in bulk, for it came to be thought of as a panacea and was also enjoyed as a social beverage with milk and sugar in European coffee houses. Indeed it was even thought to cure syphilis, and was second only to mercury in its application until it was decided that it did little to stop the ‘social disease’. If only Tom Doula had known... As an amulet, wearing pieces of the sliced root around the neck was said to aid in the pain of teething, while wearing a bag of the same was a charm to prevent general illness. In North Carolina, carrying some root pieces in one’s pocket would produce the same effect. In some African American conjure traditions, it is associated with financial affairs. Placing a piece of the root in a purse or wallet is said to prevent one’s money from running out. Interestingly enough, there are also taboo’s surrounding not just the root but the wood. To burn sassafras was deemed unlucky, and in Kentucky, it was believed that burning the wood or even leaves of the sassafras would surely cause the transgressor's mules or horses to die. It is difficult to discover where this belief originates, for it was noted among Native and settlers alike. The wood had further uses as a stirring stick for making soap in the dark of the moon and to build beds that would protect the sleeper from disturbances from witches and other evil spirits. Ships built with sassafras hulls were deemed safe from shipwreck, while chicken coops built with sassafras roosting poles were reputedly free of lice. Sassafras' fresh, fragrant leaves were also used to pack away winter clothing to keep away moths. Certain medicine men among the Cherokee also used the root magically. They would chew it and rub it upon their faces and hands after being exposed to a sick person, whether biologically or spiritually, to safeguard their own magical abilities. It functions as a cleanser of "bad" or "sick" energy. Sassafras was also an ingredient in treating the wounds caused by magical projectiles known as ga:dhidv, which are the supernatural missiles of conjurers. It is interesting to draw parallels between the medicinal uses of sassafras root as a cleanser of blood and its Cherokee uses as a cleanser of energy or spiritual contamination. Sassafras has many more ethnobotanical uses, and it is interesting to modern folk magic practitioners to note the correlations between its ability to ward off illness and pestilence as well as attract prosperity both in its medical and magical uses. The issues of safrole, the possibly carcinogenic chemical which lurks within the roots of the Sassafras is a tricky question. Undoubtedly it exists, but whether it is harmful when used as an occasional, traditionally prepared tea is the question. Check out my friend Kate's thesis on safrole if you want to get really nerdy with it, but as with most things, do your own research and see what you think. I drink it. I'm not worried. If you'd like to get the whole story folk magical story on Sassafras and other important native Appalachian roots, check out my piece, as well as the other fabulous works in the Third Volume of Verdant Gnosis. What can I make with it? Practical: Tea, syrup and confections! Boil those roots to get a deep red, lovely tea. You can also use the leaves dried and powdered like file gumbo powder to thicken soups and stews. I like to boil the roots, combine with honey and add bubbly water for a "root beer". Wood: furniture, interior and exterior joinery, windows, doors and door frames , kitchen cabinets and paneling, boat building, canoe paddles, gates, barn doors, wagon beds and fence posts. Sassafras is very resistant to heartwood decay, but in exposed damp conditions the sapwood is vulnerable to powder post beetle. Oh, and probably a fine spoon. Magical: Use the chips of root bark for protective magics or craft a bed, gate, or object to be free from the influence of malevolent spirits. Burn the wood chips as a bioregional incense to rid a place of negative influence, spirits/ persons. I like to make a "blasting rod" type wand from this wood to free places, people and objects from the sway of these spirits as well. It's twisty nature really lends it to this purpose. Works Cited:

(1) Austin, Daniel F., and P. Narodny. Honychurch. Florida Ethnobotany: Fairchild Tropical Garden, Coral Gables, Florida Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, Tucson, Arizona: With More than 500 Species Illustrated by Penelope N. Honychurch. Boca Raton, FL: CRC, 2004. Kilpatrick, Alan. The Night Has a Naked Soul. Witchcraft and Sorcery among the Western Cherokee. (Syracuse NY: Syracuse University Press, 1997). Rupp, Rebecca. Red Oaks & Black Birches: The Science and Lore of Trees. Pownal, VT: Storey Communications, 1990. Tantaquidgeon, Gladys. "Mohegan Medical Practices, Weather-lore and Superstitions." Smithsonian Institution- Bureau of Ethnology Annual Report 44 (1928): 264-70. Thomas, Daniel Lindsey, and Lucy Blayney Thomas. Kentucky Superstitions. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1920. #2993. UCLA Folklore Archives 1_6728. White and Brown. The Frank C. Brown Collection of North Carolina Folklore; the Folklore of North Carolina, Collected by Dr. Frank C. Brown during the Years 1912 to 1943, in Collaboration with the North Carolina Folklore Society. White, Newman Ivey, and Frank Clyde Brown. The Frank C. Brown Collection of North Carolina Folklore; the Folklore of North Carolina. Durham: Duke University Press [1952-64], 1952. Willard, Fred L., Victor G. Aeby, and Tracy Carpenter-Aeby. "Sassafras in the New World and the Syphilis Exchange." Journal Of Instructional Psychology 41, no. 1-4 (March 2014): 3-9. Vance, Randolph. Ozark Magic and Folklore. (New York, N.Y. : Dover Publications, 1964, c1947). Yronwode, Catherine. Hoodoo Herb and Root Magic: A Materia Magica of African-American Conjure. Lucky Mojo Curio Company: Root Doctor, 2002.

8 Comments

|

Archives

April 2024

To support me in my research and work, please consider donating. Every dollar helps!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed