|

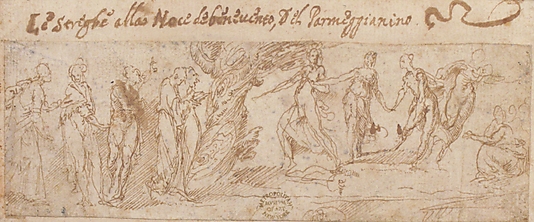

Various species of walnuts grow all over the world, but we’ll focus on our native North American species, the Eastern Black walnut (Juglans Nigra). Black walnut is one of the most valuable timber trees in our Appalachian forests, and it has a myriad of food, medicinal, lumber, and folkloric uses. The Black walnut has been in North America at least since the Pleistocene era, and has a long history of use as a food and medicine source for First Nations people in North America, and later, the rest of North America’s immigrants. Because of the beautiful, rich brown color of the heartwood, Black walnut has become one of the most valuable hardwoods native to North America. Its natural resistance to decay and insect damage have helped it remain on top in the rankings of useful woods, as well as its large size. Black walnut trees range from the East Coast to the Great Plains and from Texas and Georgia, north to central Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and up to Ontario, Canada. They have a broad range, following the deep, rich, moist forest soils. It is often found in the forest with yellow poplar, white and green ash, black cherry, basswood, beech, sugar maple, red oak, hickory, elm, hackberry, and boxelder. One of the most interesting things about Black walnuts is their poisonous nature. The tree is allelopathic, which means it releases chemicals from its roots and decaying bark and leaves that stunt other plant’s growth. Black walnuts produces Juglone, which is the allelopathic chemical that is exuded by this majestic tree. It is the tree's built in method to cut down on competition by nearby growing plants. People made note of this potent chemical as early as 77 CE and parts of the walnut have been used as herbicide, anti-fungal and anti-bacterials for centuries. Juglans means “nut of Jupiter” in latin, and some believe it refers to Jupiter’s, well...nethers. The nut may in fact refer to the “glans of Jupiter”. This may account for the walnut's connection with fertility and love in legend. The ancient Greeks apparently stewed walnuts and ate them to increase fertility. Carrying a walnut in the shell was also believed to increase fertility, an interesting practice in comparison with our Hickory and Buckeye nut lore here in Appalachia as a charm for good luck when carried on one’s person. The Romans ascribed more feminine aspects to the walnut and associated it with Juno, Jupiter’s wife and the Roman goddess of women and marriage. In fact, one of the Roman wedding customs was to throw walnuts at the bride and groom to encourage fertility. Sounds dangerous. European Walnuts feature prominently in folklore and fairy tales throughout the rest of the continent, especially in Italy. There, walnut shells are often seen to be containers for magical or precious objects. They also believed that walnut branches or wood could protect one from lightning strike. It was also sometimes called, “roots of evil” due to its poisoning nature, as well as its' links it to witches in Italian folklore. It was, after all, said that witches preferred to meet under the poisonous shade of the noxious walnut tree, one of the most famous comes from the legend of the Witches of Benevento, “Unguento, unguento portami al noce di Benevento sopra l'acqua e sopra il vento e sopra ogni altro maltempo. Unguent, unguent, Carry me to the walnut tree of Benevento, Above the water and above the wind, And above all other bad weather.” - A recitation many of the women accused of witchcraft repeated at their trials. Though not a use of the wood, I couldn’t help but mention a lovely recipe for Nocino after mentioning the Witches of Benevento. Nocino is an Italian cordial made from green walnuts picked traditionally on St. John’s Day (June 24th). It is very easy to make and you can add other tasty herbs to it to spice it up, but the dark, nutty flavor is divine. Perhaps in conjunction with its association with malevolent practices, falling asleep beneath a walnut tree was thought to cause madness or prophetic dreams; two paths one’s mind may take that often lead to one another. In Bulgarian folk beliefs, certain tasks must be undertaken in advance of planting a walnut tree to avoid premature death or becoming estranged from your loved one, combining the association it holds with poison and of love. Aside from its medieval associations with evil, in Europe the walnut was seen as promoting fertility, strengthening the heart and helping to dispel the evils of rheumatism. In North America, in the Ozarks, walnuts drew lightning, and to plant a walnut tree near one’s house was seen as a terrible idea. I wonder if this has some to do with the incessant crashing of walnuts in the fall upon the roof, rather than solely a fear that this tree, above others, draws lightning to it. Over at New World Witchery, (which is an incredible podcast and blog), Cory has done a great piece about walnut lore, and quotes Ozark Magic and Folklore to describe some folk beliefs, both magical and medicinal, about Black walnuts in the New World,

He also found in Kentucky Superstitions, “Daniel & Lucy Thomas, in their Kentucky Superstitions, say that green walnuts can be rubbed on warts, then buried to charm the wart away.” and, “Heading into Illinois, Henry Hyatt reports a mix of magical and medical uses for walnuts:

He goes into great detail about much of the lore I could repeat here, or you can go check out his post. A few other New World tidbits include the Pennsylvania Dutch who saw the Black walnut as an indicator of good soils, assuming that limestone was rich where Black walnut grew, and would choose land with healthy stands of Walnut. Some also say that Walnuts fruit best when beaten. This may be due to the fact that using sticks to knock Walnuts out of the tree was once the main method of harvest. Black walnut was abundant then, and used for rougher applications such as split rail fences and railroad ties. The upper Great Lakes region provides archeological evidence of Walnut consumption dating back to 2000 B.C.E. in North America. The people of the First Nation’s in Appalachia used Black walnut for a variety of things. The hulls were used to dye hides, baskets and other materials, while the nutritious nuts were eaten in a variety of ways, and the leaves, bark and hulls used for medicine. They also tapped the trees, much like maple, for their sap. Some tribes introduced the Black Walnut as an edible food to the colonists who arrived in droves, among many other important wild food plants. They also reportedly used the hulls and their potent juglone to stun fish in dammed creeks. The Black walnut is known today as a valuable timber tree and its wood is much revered. It has traditionally been used to make furniture, cabinets, flooring and other useful interior applications, as well as gunstocks because of it does not twist after seasoning. It is excellent, and some say the best, for turning bowls for these same reasons. It also finishes very nicely and can be stained and glued easily. The wood was also used, among other hardwoods like cherry, to make mountain dulcimers and other musical instruments. It is also excellent for sculpture and fine detail work. Black walnut was largely used in colonial times for these applications, but as mahogany gained popularity, the walnut was cut, and therefore planted out, less and less, and the Black walnut stands grew slim. What can I make with it? Practical: Beautiful bowls, spoons, utensils, cutting boards, gunstocks, furniture, knife hilts, boxes and pretty much everything else you can think of in fine woodworking. Magical: Wands, stangs, and walking sticks aligned with fertility of mind and body, for love magics, for work on the poison path, for blasting rods and/or general purpose wooden magical working tools. Bowls for holding shadow materials or dark working ingredients, or those things aligned with Jupiter. Here are two recipes from Madame Grieve for using Black Walnuts:

To preserve green Walnuts in Syrup 'Take as many green Walnuts as you please, about the middle of July, try them all with a pin, if it goes easily through them they are fit for your purpose; lay them in Water for nine days, washing and shifting them Morning and Night; then boil them in water until they be a little Soft, lay them to drain; then pierce them through with a Wooden Sciver, and in the hole put a Clove, and in some a bit of Cinnamon, and in some the rind of a Citron Candi'd: then take the weight of your Nuts in Sugar, or a little more; make it into a syrup, in which boil your Nuts (scimming them) till they be tender; then put them up in Gally potts, and cover them close. When you lay them to drain, wipe them with a Course cloth to take off a thin green Skin. They are Cordial and Stomachal.' - (From The Family Physician, 'by Geo. Hartman, Phylo Chymist, who liv'd and Travell'd with the Honourable Sir Kenelm Digby, in several parts of Europe the space of Seven Years till he died.') The next is from a seventeenth-century household MS. Receipt Book inscribed Madam Susanna Avery, Her Book, May ye 12th, Anno Domini 1688. To Pickel Wallnutts Green 'Let your nutts be green as not to have any shell; then run a kniting pin two ways through them; then put them into as much ordinary vinegar as will cover them, and let them stand thirty days, shifting them every too days in ffrech vinegar; then ginger and black peper of each ounce, rochambole two ounces slised, a handfull of bay leaves; put all togeather cold; then wrap up every wall nutt singly in a vine leaf, and put them in putt them into [sic] the ffolloing pickel: for 200 of walnutts take two gallans of the best whit vineager, a pint of the best mustard seed, fore ounces of horse radish, with six lemons sliced with the rin(d)s on, cloves and mace half an ounce, a stone jar, and put the pickel on them, and cork them close up; and they will be ffitt for use in three months, and keep too years.' Sources: Berry, Joel Brian. "History of Black Walnut." History of Black Walnut. Herbal Legacy, n.d. Web. 14 Feb. 2016. "BLACK WALNUT." Black Walnut. UCC, n.d. Web. 14 Feb. 2016. "Black Walnut Gunstock Blanks and More." What Is Black Walnut Wood and What Are Its Best Uses for Projects? The Lumber Shack, n.d. Web. 14 Feb. 2016. Cunningham, Scott. Magical Herbalism. Llewellyn Publications, 1993. Grieve, M. A Modern Herbal; the Medicinal, Culinary, Cosmetic and Economic Properties, Cultivation and Folk-lore of Herbs, Grasses, Fungi, Shrubs, & Trees with All Their Modern Scientific Uses. New York: Dover Publications, 1971. Print. Hopman, Ellen Evert. Tree Medicine Tree Magic. Phoenix Publishing Inc., 1991. Pettigrove, Cedrick. The Esoteric Codex: Supernatural Legends. Turner, Nancy Jean, and Patrick von Aderkas. "Sustained By First Nations: European Newcomers' Use Of Indigenous Plant Foods In Temperate North America." Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae 81.4 (2012): 295-315. Academic Search Complete. Web. 14 Feb. 2016. Wilson, Lisa Anne. "The Giving Walnut." Wild Culture (2014). http://walnutcouncil.org/ http://www.sacredearth.com/ethnobotany/foraging/Walnuts.php

1 Comment

We're offering a garden planning intensive at our magical urban garden. 5 -100$ sliding scale. Use our contact form to secure your space. Limit to 15 students.

The Betula family has about 60 species all together worldwide. In general they thrive in northern temperate forests where they are one of the first trees to colonize disturbed or new land, and are what is called a pioneer species: paving the way for the rest of the forest to follow. Birch has a long history of folkloric belief from many places. In Ireland, on Imbolc or Candlemas, Birch was (and still is) the wood used for the small wands that the 'Bride' or Brigid poppets made of straw were given. The twigs were also used to make a bed for this goddess-come-saint, St. Brigid, on her eve February 1st or 2nd. The words Brigid and Birch both stem from the same word, "bher(e)g" in Irish meaning "shining white". Birch saplings in general were seen to bring fruitfulness, and even to strike a person or an animal with one, especially a cow, would impart this fruitfulness to the victim. This fruitfulness could not come about without its precursor: love. In Wales, wreathes of Birch were given as a token of love. Birch was also the wood of the lover's bower, and as a twig given as a gift between lovers, it symbolized constancy. This lends the tree well to its further associations in this realm as a feature of many of the Rites of Summer. Birch was even known to be used as the wood for the Maypole in England at Beltane. While in Germany, the leafy branches of the Birch would hide the identity of a "May King" to be guessed by neighbors. Birch was not only associated with love, however, it was also believed to have strong protective and purification properties. In Ireland, twigs were placed above babies cradles to protect them in the Hebrides and in Wales, the wood was traditionally used to make the cradle itself. Birch is ironically used both as the traditional twigs in a witch's broom, and also to drive away witches. These brooms were also used to sweep out the old year around the Winter Solstice, on the day after the longest night of the year, which I think ties in nicely with the ecological niche of this tree as a pioneer species, the renewing tree, the first tree to prepare the ground for the expanding forest. Bundles of birch twigs were also used to "beat the bounds" around churches and send demons and unclean spirits a-running. In Ireland, the Fae were said to dislike Birch, so not only did it protect from demons, but meddling fairies as well. The bundle of birch twigs, known as a Ruten, is also carried by the infamous Krampus of the Alpine region as a means to discipline naughty children. Maurice Bruce write in, "The Krampus in Styria", "There seems to be little doubt as to his true identity for, in no other form is the full regalia of the Horned God of the Witches so well preserved. The birch—apart from its phallic significance—may have a connection with the initiation rites of certain witch-covens; rites which entailed binding and scourging as a form of mock-death. The chains could have been introduced in a Christian attempt to 'bind the Devil' but again they could be a remnant of pagan initiation rites." He also goes on to say, "Small gold-painted birch bundles are often presented by Krampus to each family. The birches are hung on a wall as a form of decoration and seem to be renewed each year particularly in those houses where the behaviour of the children merits the application of corporal correction." According to Charles M. Skinner, Birch it was also believed to protect from lightening-strike, wounds, barrenness, gout, the evil eye and even caterpillars. In Germany, aside from the feral Krampus, the Birch is associated with the Wild Woman of the Woods as well. In folklore The Lady entices a shepherdess to leave her spinning and dance with her by dazzling her with her white gleaming attire. After three days of dancing she fills the poor woman's pockets with birch leaves which turn to gold as soon as she arrives back home. This story mirrors that of the Germanic goddesses Frau Holle and her lesser known cousin Perchta. They are known for their rewarding of hard workers, especially that of the industrious, poor young woman who diligently spins. In Russia, Skinner mentions that the Birch was seen as a masculine entity and to summon him a simple ritual is done by cutting down Birch saplings and placing them point inwards in a circle. One then stands in the center and calls him forth to be granted favors by him, so long as you don't mind parting with your immortal soul in return. (Though I cannot find the source of this claim other than in Skinner's book, so please, if anyone knows more about this, I'd love to find more sources.) Practically, Birch was used in Ireland for bark tanning leather, preserving fishing lines, and making brooms. The dense, straight grained wood made it useful for making everything from toys to bobbins, spools and reels for working with textiles. In Scotland it was used for agricultural tools, building material and for all manner of household things due to its abundance. The Black or Sweet Birch (Betula lenta), which we have in abundance in Appalachia, was extracted to make Birch oil (also known as wintergreen oil), a flavoring agent you might recognize from old fashioned root and birch beers. Birch sap all on its own is a traditional drink in Northern Europe, Russia, and Northern China. In Russia, they not only drank the sap for pleasure, but also as a cure for consumption. It was also used as a lubricant, and the bark was used as a torch, as well as a cleanser in the form of steam in bath houses and saunas. The sap can also be used to make birch syrup, but its ratio of sap to finished syrup is much higher than maple, making it an arduous process. You can also extract Birch tar at home to use as a traditional bonding agent, fuel, medicine, waterproofing, leather treatment and wood preserver. Birch wood can also be used to smoke foods like herring. It makes a fine firewood and burns well even when damp due to its oil content. Ground Birch bark was fermented in sea water and used for seasoning the woolen, hemp or linen sails and hemp ropes of traditional Norwegian boats. The bark was also sometimes cordaged into wicks for burning like candles, and the twigs were used to make functional brooms, or besomes. Striking criminals with bundles of birch twigs also eventually became a form of corporeal punishment known as Birching. In legend, it was even said Christ himself was beaten with Birch rods. Different First Nations people used Birch in a variety of ways, but the Birch bark was especially useful for containers, canoes, and many other uses. They used a variety of species for bark harvest, such as Black or Sweet Birch (Betula lenta), Yellow Birch (Betula alleghaniensis), Paper Birch (Betula papyrifera) and a few others. Birch twigs and branches also made fine wattle for structure building, as well as thatch for roofing. In Appalachia, Birches were used for much of the same as elsewhere. Birch oil was made from Black Birch, containers made from various species' bark, and carved wares and furniture made from the lumber. A special bioregional note, however, is that our Yellow Birch houses the mystical Chaga mushroom (Inonotus obliquus), which is an amazing adaptogen that has active components for antioxidant, antitumoral, and antiviral activities and for improving human immunity against infection of pathogenic microbes. Please remember though, Chaga is a rare find, and a precious one at that. Always harvest from the forest wisely, or choose other immune supporting mushrooms likes Turkey tail and Reishi which are more common to sustainably wildcraft. What can I make with it? Practical: Kuksa cups, spoons, bowls, toys, brooms, and buildings. With the Paper Birch and other birch species that have bark which peels well, one can make a plethora of useful and beautiful objects, such as containers, paper, and shingles, but we will look at that in another post. Keep in mind when harvesting that when you remove the bark from a tree, you kill it. Magical: Wands for magic concerned with love, protection, purification, The Woman of the Woods, and new beginnings. Also stangs, staffs, and besomes for the Rites of Summer, as well as small, detailed ritual carvings or jewelry. Sources: Bruce, Maurice. “The Krampus in Styria”. Folklore 69.1 (1958): 45–47. Web... Coitir, Niall Mac, and Grania Langrishe. Irish Trees: Myths, Legends and Folklore. Cork: Collins, 2003. Print. Hageneder, Fred. The Meaning of Trees: Botany, History, Healing, Lore. San Francisco: Chronicle, 2005. Print. Kendall, Paul. "Birch." Mythology and Folklore . Trees for Life, n.d. Web. 02 Feb. 2016. Loudon, J. C. An Encyclopedia of Trees and Shrubs; Being the Arboretum Et Fruticetum Britannicum Abridged: Containing the Hardy Trees and Shrubs of Britain Native and Foreign, Scientifically and Popularly Described; with Their Propagation, Culture, and Uses in the Arts; and with Engravings of Nearly All Species. Abridged from the Large Edition in Eight Volumes, and Adapted for the Use of Nurserymen, Gardeners, and Foresters. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1842. Print. Moerman, Daniel E. Native American Ethnobotany. Portland: Timber, 1998. Print. Skinner, Charles M. Myths and Legends of Flowers, Trees, Fruits, and Plants: In All Ages and All Climes. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1939. Print. http://appalachianagroforestry.com/bio-regional-ecology/understanding-appalachia/

|

Archives

April 2024

To support me in my research and work, please consider donating. Every dollar helps!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed