|

Virgula divina. (Diving Rods) "Some Sorcerers do boast they have a Rod, Gather'd with Vowes and Sacrifice, And (borne about) will strangely nod To hidden Treasure where it lies; Mankind is (sure) that Rod divine, For to the Wealthiest (ever) they incline." -Sam Shepard 1651 It's been a little while. Things have been dreamed, feasts have been eaten and winter is taking its hold down here in our corner of the world. While walking along one of our favorite places on the Laurel River, my lovely husband pointed out an odd tree and asked me what it was. It was bare branched like many other November trees, but it was covered in yellow, spidery blossoms. It was witch hazel, (Hamamelis virginiana L.) Witch hazel is one of our amazing native medicinals here in Appalachia, and has a few unique properties that I think really make it a true witches tree. Not only does it look witchy with its small, gnarly shape, but it tells you unabashedly about its magic by where and how it grows. It tends to grow along waterways and in moist, shaded areas of the Appalachian forests. It even ejects its seeds, sometimes audibly, through a process called ballistichory. It also flowers in late fall, early winter, going against the seemingly preferred methods of normal plant life cycles. If that isn't mystical, I don't know what is. The connections between witch hazel and water go deeper than preferred habitat. Witch hazel rods and forked twigs have been used by "water witches" for a very long time to locate underground wells and water sources. Because the witch hazel is native to the United States, its use as a divining rod is a uniquely North American magical practice. The American Society of Dowser's describes the history of searching for things with forked sticks as having begun in pre-history throughout the world, but as far as modern usage, the first time the word "dowsing" was used, " ...it seemingly made its first official appearance in 1650 in an essay written by the famous English Philosopher John Locke whose noble writings inspired the framers of our own Declaration of Independence and The Constitution of the United States. In his essay, Locke wrote that by the use of the dowsing rod, one could devise or discover water and precious minerals (such as gold & silver and mineral ore) Locke has appropriated his phrase from the long dead English west country language of Cornwall - where in Cornish Dewsys meant "Goddess", and "Rhod" meant tree branch, and from which he "coined" the phrase - Dowsing Rod." It had been written about prior, even by Martin Luther himself, "Dowsing as practiced today may have originated in Germany during the 15th century, when it was used in attempts to find metals. As early as 1518 Martin Luther listed dowsing for metals as an act that broke the first commandment (i.e., as occultism)." Even though it seems dowsing was practiced by Europeans since the dark ages, there is conflicting information about whether or not European settlers learned to use the witch hazel as a divining rod from the Mohegan people, or if the Mogehans learned it from the Europeans. Either way, it was and still is used by many, both Native and Settler, as the twig of choice to locate water. It appears that the term "witch hazel" was also used before ascribing it to the Hamamelis shrub in North America. The word "witch" appeared as "wych" around the 1540's and was generally taken to mean "having plaint stems". It began as a common name for European plants. It is seen in Shakespeare's Henry VIII describing a wood one can make a bow out of, which was probably the hornbeam (Corylus), another tree with pliable branches. Hamamelis was first equated with witch hazel around 1760 to describe the American plant. So to dig a little deeper into the early American historical aspects of this witchy shrub, we see that it was also known as "pistacio". The seeds were considered edible (they are) and many tribes used them as food, and also as sacred beads (as in the case of the Menomini peoples). It was also fashioned into little crosses and hung around the house for protection by colonists. This reminded me of when my husband and I recently went to England and saw all the little Rowan crosses made with red thread. The little inscription next to them in their glass case at the Pitts Rivers Museum in Oxford said they were carried about in the pocket by a local man for protection. So it seems plausible the two practices are related. Witch hazel's folkloric uses are amazingly interesting, but its medicinal uses are what makes it one of the few plants that almost every person has heard of, and it is still available in regular grocery stores and pharmacies for use today. The Cherokee used the infusion (twigs and leaves boiled in water) for bruises, tuberculosis, colds and sore throats. The Iroquois used it for dysentery, asthma, cholera, arthritis, kidney problems and to purify the blood. Many other Native peoples used witch hazel for similar things, namely celebrating its astringent properties. Colonists used it for menstrual troubles as well.

Today, we know that witch hazel's astringent tannins are what makes it a useful medicine. It is used externally for inflamed skin, piles, hemorrhoids insect bites, poison ivy and other inflammatory conditions in the forms of lotions made from distilled twigs, leaves and bark in alcohol. It has been used internally for similar purposes, namely stopping internal bleeding and bloody dysentery. I myself use it as a post face wash lotion and poison ivy remedy, and I think it is quite effective. Since the opening of the Dickinson witch hazel distillery in 1866 in Connecticut, witch hazel has continued to be an affordable medicine in the cabinets of those inclined to trust home remedies and simple cures. If you live in the Southeast, go out and see if you can spot the splash of bright yellow among the trees and witness the unique beauty that is Hamamelis virginiana in flower, in winter. Sources: Anthony Cavender. Folk Medicine in Southern Appalachia. 2003. Daniel F. Austin. Florida Ethnobotany. 2004. J.T. Garrett.The Cherokee Herbal. 2003. http://appvoices.org/2007/04/25/2895/ http://newworldwitchery.com/2011/10/27/blog-post-141-%E2%80%93-witch-hazel/ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dowsing

0 Comments

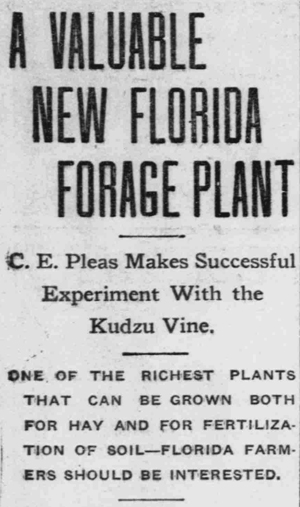

Happy Samhain everyone! I wanted to talk about a plant today that I love, Kudzu. It's on my mind after teaching a class for the Ashevillage Urban Farming Program last week on Kudzu Basket making, I fell in love again. SO, here's the dirt on Kudzu, or P. montana (among other varieties). Just to be clear, the name kudzu describes one or more species in the genus Pueraria that are closely related, and some of them are considered to be actual varieties rather than fully separate species. Interestingly enough, they are not very different physiologically and they can breed with each other. The introduced kudzu populations in the United States also have ancestry from more than one of the species. They are: P. montana, P. lobata (P. montana var. lobata) P. edulis, P. phaseoloides, P. thomsonii (P. montana var. chinensis), P. tuberosa Kudzu is synonymous with the unwanted in the southern United States where I live. It is a pest, a nuisance and an invasive. While it is true that Kudzu has dramatically changed the Southeastern landscape, it also has many unrealized and often forgotten uses. This is by no means a call out to plant it on your land, but where its hold is strong, one can harvest fodder, crafting material, building material, medicine and food. Kudzu was introduced to the United States in 1876 at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It’s lovely flowers and stately leaves impressed American gardeners. In the 1920’s, Florida nursery operators Charles and Lillie Pleas promoted its use for forage. Their Glen Arden Nursery in Chipley sold kudzu plants through the mail. During the Great Depression of the 1930’s, the Soil Conservation Service promoted kudzu for erosion control. Hundreds of young men were given work planting kudzu through the Civilian Conservation Corps. Farmers were paid as much as eight dollars an acre as incentive to plant fields of the vines in the 1940’s. As we have seen, the widespread planting of Kudzu had unintended consequences. Kudzu’s incredible growth rate lead to its take over of the southern forest edges, pulling down trees and smothering other plants.Today, Kudzu is treated much like Japanese Knotweed, another import gone awry. It is destroyed on sight usually by chemical means. It is true that these plants can take over areas when left to their own devices, but this does not mean that while these plants are here, we cannot benefit from their presence. Kudzu’s unique physiology and nutritive properties make it useful in many areas of self sufficient and sustainable living practices. Fodder Kudzu had a brief time in the limelight as a well touted forage crop for all livestock, especially ruminants. Kudzu was grown for pasture, hay, and silage. It is palatable to all types of livestock and Kudzu is nearly equal to alfalfa in nutritive value. Kudzu forage is a good feed for cattle, sheep and goats. It can be grazed, cut for hay or mixed with grass to make good quality silage. Forage yield is about 5t/ha/year when grown on fertile soil. Its overall chemical composition (roots, stems and foliage) and digestion characteristics are comparable to other commonly fed forages. It has also proven to be a great feed for dairy cattle. In goats, it is reported to maintain .35 lbs/ body weight gain /animal/ day growth (that's great!). Kudzu forage can be a good substitute for alfalfa hay in pigs and poultry. It can be included in rabbit diets that contain energy sources such as cassava, sorghum or other oil rich seed meals as well. All in all, it is comparable to alfalfa in its use as forage. It is also much less expensive, or free if you are willing to harvest it yourself. Selling cut and dried kudzu as an affordable fodder is also a market that has yet to be taken much advantage of. Kudzu will provide a good ground cover which is long-lived, if not overgrazed or mowed too often, in two to three years. It makes a good coarse hay, retaining its leaves after cutting, does not shed an appreciable amount of leaves during growing season,and it can be fed with very little waste. Kudzu with its heavy viney growth is difficult to cut, particularly the first time, because the vines catch on the divider board of an ordinary mower; modified mowers have been developed just for this purpose. Hay should be harvested when vines and the ground are dry. Leave the hay in swath for several hours before windrowing. The following morning when the dew is off, cut plants should be put in small stacks or turned, and in the afternoon it should be put up in a barn or baled. Kudzu can make a good pasture, wherein steers can gain more than 3.3 lbs/day. Do not graze plants until third year. If growth is vigorous, it may be grazed lightly the second year. For maximum production and utilization, rotation should be employed. Livestock should be taken from pasture before growth starts in spring. Kudzu is prone to overgrazing so take care on young stands not to let them be eaten to nothing. Conversely, if you need to get rid of stand, let your creatures graze away! Medicine Kudzu has been used as a medicine for thousands of years in the East and is currently being researched for its medicinal value today. Known as ge-gen in Chinese medicine, the earliest known writing about kudzu as a medicine dates back to 100 AD. In traditional Chinese medicine it is used to treat dysentery, allergies, migraine headaches, diarrhea, fevers, colds, intestinal problems and angina pectoris, to help with the digestion of food and reduce blood pressure. One of kudzu’s more fascinating traditional uses is that it has served as a treatment for alcoholism, and this has become a main focus of modern kudzu medical research today. Its use as a valuable dietary supplement for metabolic syndrome, a condition that affects 50 million Americans, is also promising according to researchers at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. In findings published in the latest Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry, studies on animals showed that substances called isoflavones found in kudzu root improved regulation of contributors to metabolic syndrome, including blood pressure, high cholesterol and blood glucose. One particular isoflavone, called puerarin is found only in kudzu and seems to be the one with the greatest beneficial effect. J. Michael Wyss, Ph.D., a professor of in the UAB Department of Cell Biology and lead author on the study said the greatest effect was in its ability to regulate glucose, or sugar, in the blood. "Puerarin, or kudzu root, may prove to be a strong complement to existing medications for insulin regulation or blood pressure, for example," said Jeevan Prasain, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the UAB Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology and a study co-author. "Physicians may be able to lower dosages of such drugs, making them more tolerable and cheaper." Kudzu also contains several other medically important chemicals such as daidzen, used to fight inflammation and microbial infections, dilute coronary arteries, relax muscles, and promote estrous cycles. It also contains daidzin, which is used to prevent cancer, and genistein, an anti-leukemic. Overall kudzu is not only an important free or low cost fodder, but it is also a useful medicine worth further examination. Kudzu has not been around long enough to become an integral part of the folk medicine practices of the Southeast, but I think it should be, since it may be here with us for awhile. Food Aside from being palatable to animals, kudzu is also an edible plant to humans. The leaves, vine tips, flowers, and roots are edible; the vines are not. The leaves can be used like spinach and eaten raw, chopped up and baked, cooked like collards, or deep fried. The young leaves can be consumed as a green, or juiced. They can be dried and made into a tea. Shoots can be eaten like asparagus. The blossom can be used to make pickles or a jelly — a taste between apple and peach. Older leaves can be fried like potato chips, or used to wrap food for storage or cooking. The root is also full of edible starch. ou can make a salad, stew the roots, batter-fry the flowers or pickled them or make a make syrup. Raw roots can be cooked in a fire, roots stripped of their outer bark can be roasted in an oven like any root vegetable; or grated and ground into a flour to make a thickener, a cream or tofu.. Only the seeds are not edible. It is best to gather shoots in spring, young leaves anytime, blossoms July through October, and roots best in fall or early spring.

Crafts and Building Materials. Other Uses Kudzu vines make a high quality bast fiber that has been used for about 750 years by artisans and weavers throughout East Asia. The fibers are extracted by hand and are translucent and generally considered finer than silk and quite strong. Kudzu is also very useful as a basket and container making material. It can be woven by hand and is easily harvested as an essentially abundant free, craft supply. Many people are beginning to tap into the beauty of kudzu baskets in the Southeastern United States and sell the baskets in stores and online. It can be a valuable material for crafts persons looking for an inexpensive, useful craft to pursue. Building with kudzu has not been done extensively in the United States, but with the rise in popularity and practicality of green building practices, kudzu bales can find a place as a useful wall mass material as well. So after all that, I hope I've provided enough evidence to at least give Kudzu a chance. While it doesn't have a strong history of use as a magical plant, I think the best use for it metaphysically is to add it to spell work for perseverance and proliferation. Use in times of weakness of heart and in times of grand designs of the mind. Let Kudzu help you grow a "mile-a-minute". Sources: Aoyagi, Akiko and William Shurtleff. “The Book of Kudzu”. Autumn Press. 1977. http://www.feedipedia.org/node/11546 James A. Duke. 1983. Handbook of Energy Crops. unpublished. http://geography.about.com/library/misc/uckudzu.htm http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/releases/162919.php http://www.columbia.edu/itc/cerc/danoffburg/invasion_bio/inv_spp_summ/Pueraria_montana.html http://www.eattheweeds.com/kudzu-pueraria-montana-var-lobata-fried-2/ http://www.knowitall.org/naturalstate/html/acc-fa/N-Basket/khouse.cfm Photos: http://library.sc.edu/blogs/newspaper/page/2/ http://georgeb.empowernetwork.com/blog/kudzu-a-good-idea-that-went-wrong |

Archives

April 2024

To support me in my research and work, please consider donating. Every dollar helps!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed