Blog

Passing Through the Brambles: Blackberry in Appalachian Folk Magic

The Appalachian folklore and folk magic of blackberries.

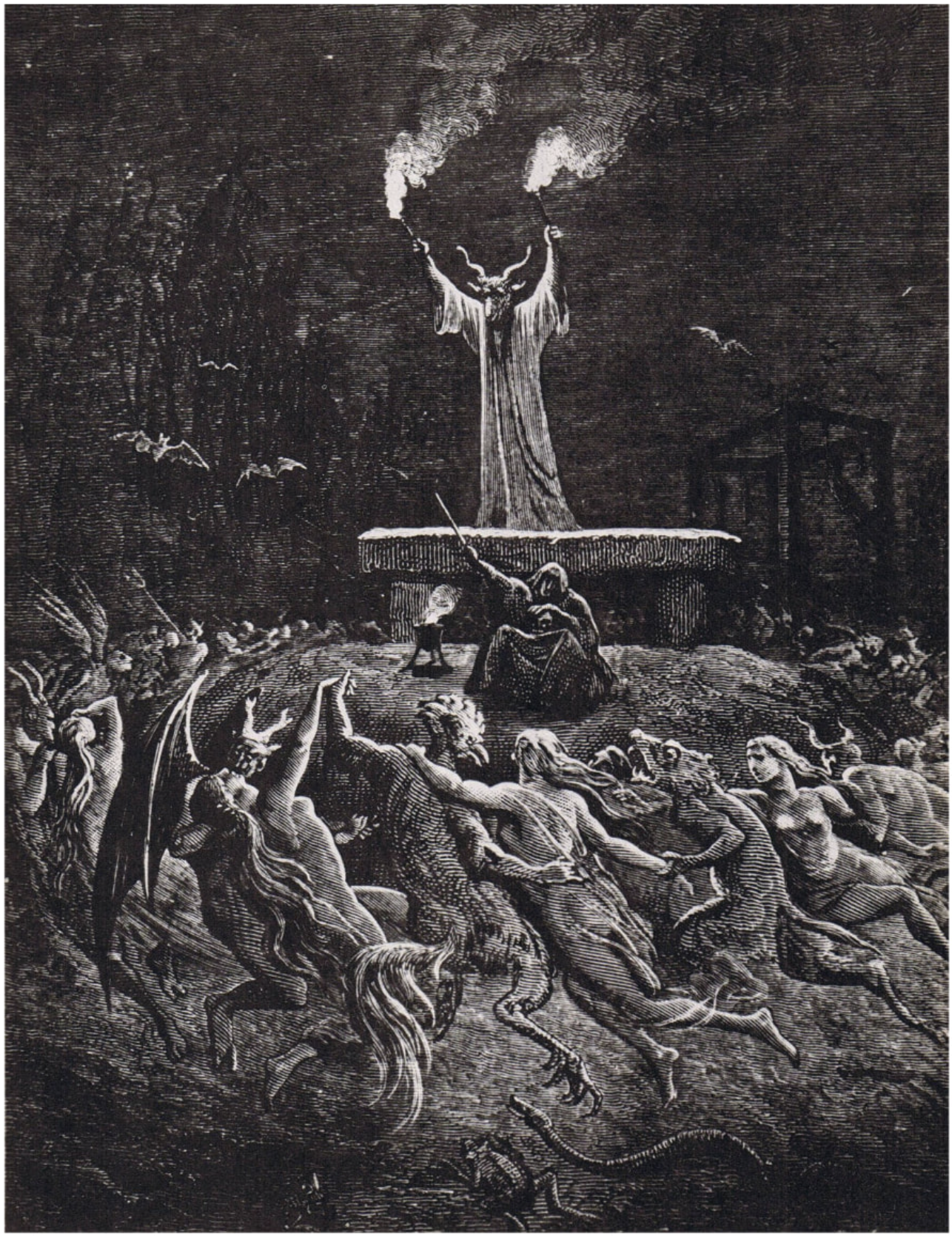

Walpurgisnacht Herblore

The historical folklore of the herbs associated with Walpurgisnacht.

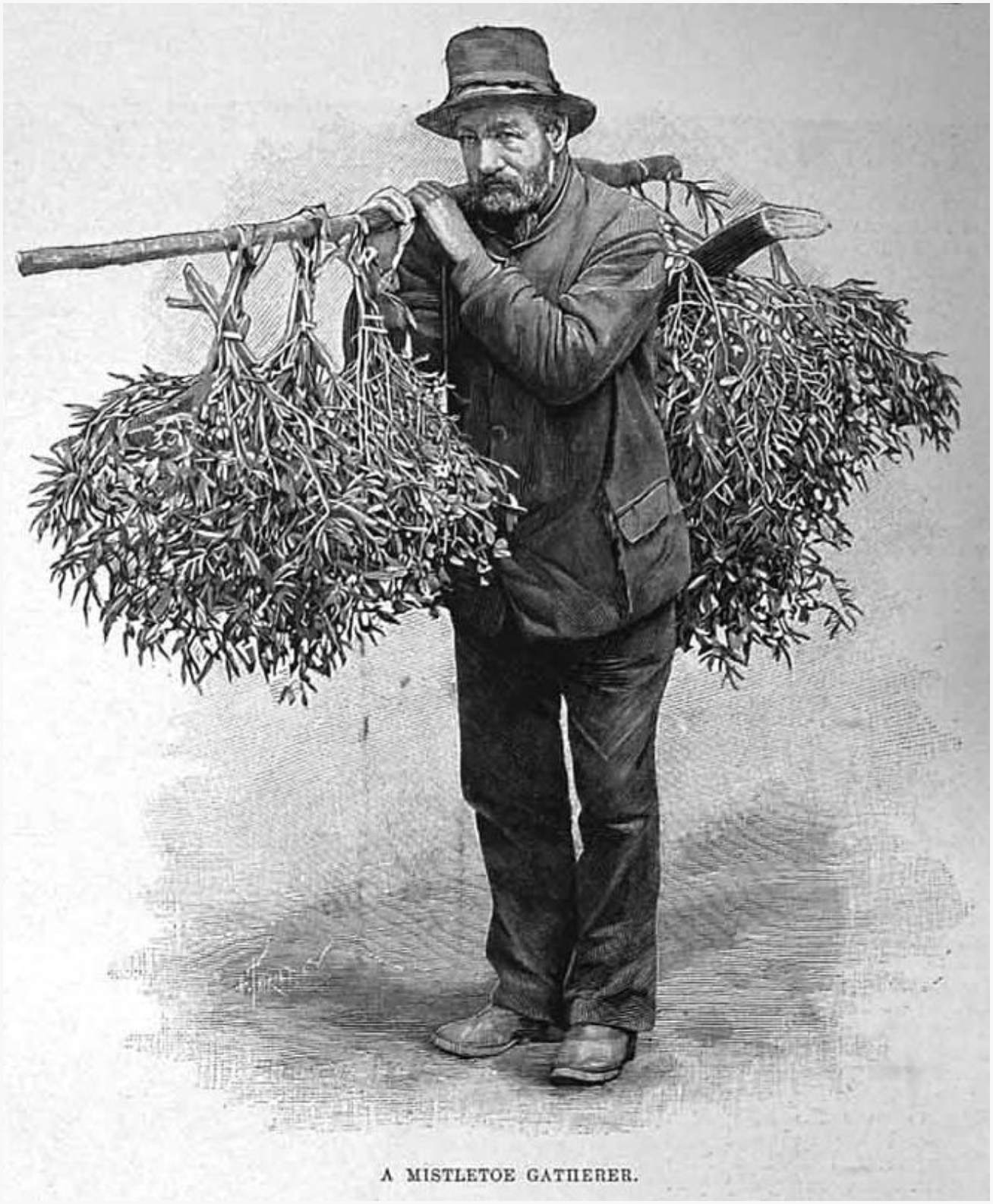

The Time Between: Appalachian Winter Lore

Appalachian Old Christmas and Appalachian winter folklore.

Life Everlasting and the Beauty of Rabbit Tobacco

The Appalachian folk magic and folk herbal uses of Rabbit Tobacco.

The Questions of Smoke: Burning Plants and Cultural Appropriation

Smoke plants to address cultural appropriation.

Persimmons and String: Respiratory Infections in Appalachian Folk Medicine and Magic

Respiratory Infections in Appalachian Folk Medicine and Magic.