|

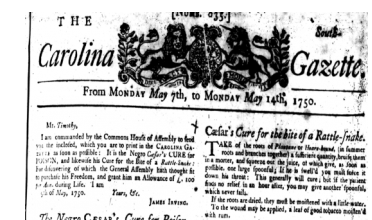

It finally feels like Fall here in the mountains, and today I've been able to wear long sleeves for the first time without having to change at noon into something cooler. I've been hard at work with Abby Artemisia putting together our new Folk School for next year, the Sassafras School of Appalachian Herbalism. Check it out! Aside from all those projects I've been winding down to the last Hedgecraft class November 17th and already have an almost full waiting list for 2019's Hedgecraft! I am thrilled so many people are so interested in Cottage Craft and Old Ways. So housekeeping aside, I'd like to explore some of the lore of Plantain... "Romeo and Juliet"(i. 2):-- "Benvolio. Take thou some new infection to thy eye, And the rank poison of the old will die. Romeo. Your plantain leaf is excellent for that. Benvolio. For what, I pray thee? Romeo. For your broken skin." The time of Shakespeare seems like a long time ago now, but plants in the Plantago genus have been used as medicine for a long, long time by people all over the world. The Plantago genus has 275 species worldwide, which as we’ll see, thank the gods, because it basically was used for everything. Though their uses are numerous, we’ll focus on Broadleaf plantain, Plantago major, and Narrow leaf or ribwort plantain, p.lanceolata, because those are our two most abundant here in the Mountains of WNC and are present everywhere in North America except the Arctic. I’ll refer to both throughout this post. It’s hard to know where to begin with Plantain. It has so many uses, but one that most people know it for is its wound healing abilities. It’s been used around the world for wounds, burns, and ulcers to stop bleeding, absorb infection and generally treat the nasty sorts of things that can happen to a body. Norwegians and Swedes call this plant ‘groblad’, which can be translated as ‘healing leaves’. Crushed fresh leaves and juice applied directly to wounds is mentioned in the ethnobotany of many countries and cultures from Russia to India. Through its long history of use worldwide as well as information gathered from the many studies done upon these plants, we know the crushed leaves have styptic, antioxidant, antimicrobial, antifungal, antibacterial , analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and immunomodulation, just to name a few. We can see from the pollen record that Broadleaf plantain (P. major) entered the Nordic lands around 4000 years ago, and from Europe, spread almost worldwide. It is one of the herbs mentioned in the Nine Herbs Charm, from the 10th century, was gathered from Anglo-Saxon England, and was used to treat infection and poisoning. Plantain was known as Weybroed or waybread. You can learn the charm yourself here: The Nine Herbs Charm. The other herbs referenced in this charm were: Mugwort, Chamomile, Nettle, Crabapple, Thyme, Betony, Lamb's Cress, and Fennel. Though there is debate here and there about a few of the plant’s identities. This is one part magical recitation, one part effective, healing herbs. The poem is also amazing because it is one of two known references to Woden (or Odin) in Old English poetry, an old god of the Nordic peoples. It was used extensively for many purposes beyond wound healing throughout Europe and Asia, but once again, the places where plant histories overlap throughout different cultures always delights me. Everywhere Europeans went, it followed. Sort of like a plant marker of European colonization. This is one of the reasons certain Indigenous peoples in North America came to call it, “White man’s footprint.” Sometimes I think of this fact when I look upon p.major, but I can’t blame this plant for the terrible things done by my ancestors. It more then makes up for this association with its ready availability, ease of harvest and amazing medicine and food. I want things to be right and wrong, good and evil. It’s simpler that way. But it is never that way. Never simple. Always nuanced. Always complex. Mentioned throughout the world in medical writings from Greece to Medieval Islamic Spain, it was used as crushed whole leaves, or mixed with honey for wounds. It was believed it could heal any organ in the human body when boiled in butter and eaten. I cannot argue against adding butter to everything to make it better. Culpepper said in his “Complete Herbal” (1649) P. major is under Venus: ‘It cures the head by its antipathy to Mars and the privities by its sympathy to Venus. There is not a martial disease that it does not cure’. About the medicinal effects he wrote: ‘It is good to stay spitting of blood and bleedings at the mouth, or the making of foul and bloody water, by reason of any ulcer in the reins or bladder’. It was even believed that animals could use the plantain to heal themselves. Here's a story about the plantain from a the 1798 edition of The Farmer's Almanack: “A toad was seen fighting with a spider in Rhode-Island; and when the former was bit, it hopped to a plantain leaf, bit off a piece, and then engaged with the spider again. After this had been repeated sundry times, a spectator pulled up the plantain, and put it out of the way. The toad, on being bit again, jumped to where the plantain had stood; and as it was not to be found, she hopped round several times, turned over on her back, swelled up, and died immediately. This is an evident demonstration that the juice of the plantain is an antidote against the bites of those venomous insects.” In Southern Folk Medicine (1999) we get the following recipe for dysentery: “For a Purging: First of all upon its first coming take a plenty of Chicken water. If it continues take a dose of Hippo if that don't stop it take a dose of Rhubarb and if it continues after that take the following decoction—Persimon roote, Yarrow, plantain, blackberry roots, Gumm leaves and a little red oak Bark boild one 3rd part away add a little brandy and sugar and drink it at discretion.” The astringent Red Oak bark and Persimmon root bark, the uses of which were surely gleaned from the Cherokee and other indigenous folks in the region, were both used often for diarrhea in Appalachian and the broader Southern Folk Medicine Tradition. All the other drying and astringent plants, the blackberry, Gum and yarrow, could definitely use the soothing of the plantain to provide a powerful remedy for this at time ubiquitous problem, especially in Summer. This is one reason that in the South, the “summer complaint” has so many folk remedies. In Appalachian folk medicine in general, plantain was used to bring boils to head, applied to burns and wounds, fried in lard to make poultices, and to generally “draw out poison”. More people in the herb world are finally having conversations today about the lack of visibility around the specific Indigenous medicines shared with colonists and especially the contributions of African and Caribbean people’s knowledge and plant uses to herbalism in general. In the South I see this is especially present. If people weren’t able to use their native plants, of which some they DID still have access too, they were still pioneering and adapting their own healing knowledge base and using what was around them. It is always important to note, that folk medicine is not a stuck or static practice, but it constantly evolving and changing. The story of Caesar’s cure for poison is a well documented example of how despite slavery, black folks were still pioneering and experimenting with plants, wherever they were. Here are some people doing work around the contributions of POC in herbal healing: (Reminder, please don't ask POC herbalists to "prove" to you the contributions of African people to Appalachian or Southern Folk Medicine or Western Herbalism in general. Why would you ask that? Really, why? What is your goal here? If you have a question about specific academic sources etc., I have come across a lot in my research and I am happy to share them with you if you just have to have them. Just please don't bother POC herbalists about this.) School of Liberation, Healing and Medicine Sade Musa (who complied this list below) Queering Herbalism's POC Healers List Ayo Ngozi Well of Indigenous Wisdom Plantain is sometimes known as snakeroot or snakeweed and was used by Appalachians and people of the Deep South of all races for snake bite. And it was an African slave named Caesar who discovered this use and how to best fix it. It was so effective he was remarkably rewarded for his discovery and was set free by the South Carolina General Assembly in 1750 and allotted £100 per year for duration of his life. Something almost unheard of. And here is the healer Caesar’s Cure: “Take the Roots of plantain and hoarhound fresh or dried 3 ounces boil them together in two quarts of water to one quart and strain it of this decoction let the patient take one third part three mornings fasting successively, from which if he finds any relief it must be continued till he is perfectly recovered; on the Contrary if he finds no Alteration after the first dose it is a sign that the patient has either not been poisoned at all, or that it is such a poison as Cesars antidotes will not Remedy (so may leave off the decoction).” (Southern Folk Medicine, p.12) Plantain is clearly a medicine to celebrate. It’s also a food to celebrate! Rich in Vitamic C, K1 and carotenoids, this plant has edible leaves, seed stalks and seeds. It is also interesting to note that the leaves are low in oxalic acid, which can be irritating to some people with kidney stones or certain autoimmune conditions. In early Spring, add some fresh young leaves to salads or sautes and enjoy. My favorite thing to do with tougher older leaves is to do a quick fry in coconut oil or lard and make plantain chips. Like kale chips, but a slightly different texture. Crunchy and amazing. I just had some for breakfast with my roasted sweet taters and chicken, sauteed in a little water to soften them up, and finished in ghee from my loves at Goddess Ghee. Magically, the seed stalks were used in love divinations. In people throughout Western Europe would strip the stalks of flowers and if the next day some still persisted, it meant the prospect of a marriage was good. Much like Mullein, the stalks were also bent or broken and it they grew back or upright it meant your true love returned your affections. When children in Cheshire England see the first Plantain stalk they say this rhyme for good luck, “Chimney sweeper all in black, go to the brooke and wash your back, wash it clean or wash it none, Chimney sweeper have you done?” (Dyer, 1889) It is also interesting that Plantain also has a St John’s Eve association much like its sister herb Mugwort, and were both said in Europe that a rare ‘coal’ exists under the roots at noon or midnight on St. John’s eve and if one can find it and wear it, they shall be protected against plague and carbuncles, fever and ague. So plantain can heal your wounds and whisper the secrets of your true love’s heart? I’ll add some more to my quiche thanks. I've been having fun making a concoction known as Succus: juicing plantain and then adding the same amount of honey. (Succus can also just be the plain juice). It's great by the teaspoon for coughs, dry respiratory conditions, and as a wound dressing. I store this nasty goodness in the fridge. But it’s hard to resist our urge to categorize things as BAD or GOOD, HELPFUL or BANEFUL. It’s hard for us to just let things BE what they are right now. Plantain has invited me to be ok with where I am right now, complicated, painful stories, cruel acts, ancestral trauma, bright moments and joy, successes, all the things mixed together that have made me ME. Thank you Plantago. Works Cited:

Blair, K. (2014). The wild wisdom of weeds: 13 essential plants for human survival. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing. Dyer, T.S. Thistleton. The Folklore of Plants. 1889. Jarić, Snežana, et al. “Traditional Wound-Healing Plants Used in the Balkan Region (Southeast Europe).” Journal of Ethnopharmacology, vol. 211, Jan. 2018, pp. 311–328. Moss, Kay. Southern Folk Medicine, 1750-1820. University of South Carolina Press, 1999. Samuelsen, A. B. The traditional uses, chemical constituents and biological activities of Plantago major L. A review. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 1 jan. 2000. v. 71, p. 1–21. Sieling, Peter. “Chapter Five: Appalachian Folk Remedies.” Folk Medicine, Jan. 2003, p. 20. Watts, Donald. Dictionary Of Plant Lore. Amsterdam: Academic Press, 2007. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost).

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

April 2024

To support me in my research and work, please consider donating. Every dollar helps!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed