|

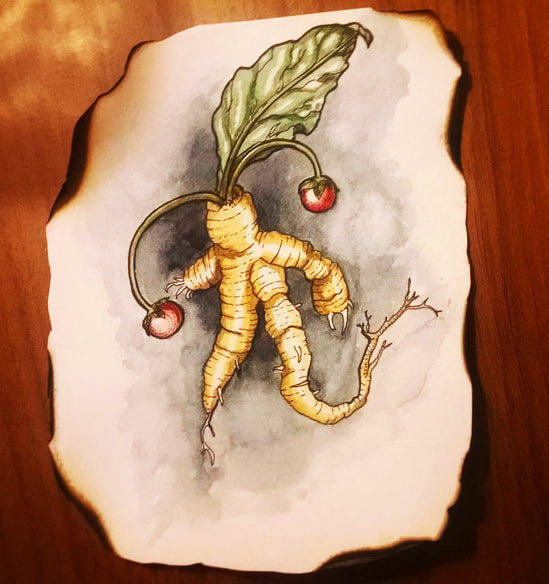

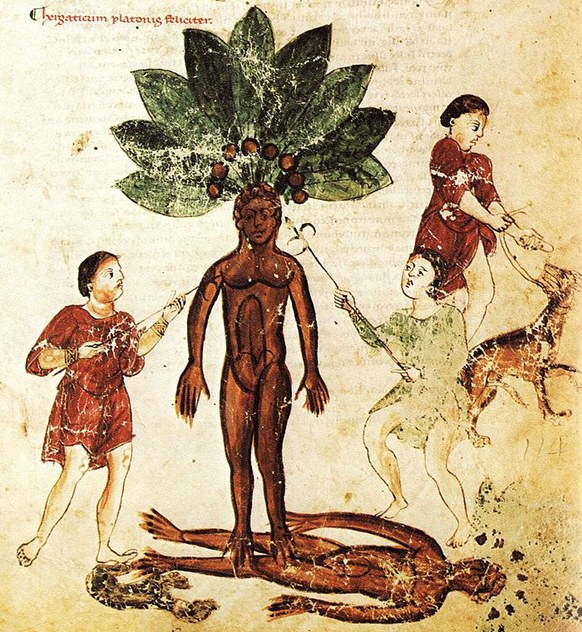

I talk a lot about the plants of Appalachia, but the other day my friend Augustus Rushing asked me about mandrake. My face lit up, and I excitedly barfed out all the things that get me stoked about this most storied of plants. For truly, there is not a plant more deeply entrenched in withlore than this one... Mandragora officinarum. This root is so shrouded in mystery and folklore it may be considered the most infamous of the witch’s plants. Though not the most toxic of the solanaceae, it certainly could be said to have been regarded as one of the most powerful and frightening of them all. It hails from the Eastern Mediterranean. The Egyptians were familiar with the plant and used the roots and berries for various medicinal purposes, but namely as an aphrodisiac. Pieces of the roots were found in burial chambers and the plant is mentioned in the famous Ebers Papyrus from between 1700-1600 B.C. It is also mentioned in the Bible twice. Once when Rachel barters for them with Leah to become fertile, and again in reference to love-making between the young Shulammite and her beloved. Clearly, this root fascinated many, and it comes as no surprise that it should be so titillating and tempting when associated with all sorts of sordid and forbidden acts. The oldest written mention of the mandrake occurs in the cuneiform tablets of the Assyrians and the Old Testament. It may have been referring to mandrake wine, which was often mentioned in later tablets. The Greek doctor Theophrastus discussed its uses as a soporific and aphrodisiac, but more interestingly, he described curious rituals that were performed before the harvest of the alluring root. It required three circles to be drawn with a knife in the earth around the plant, after which the top of the plant was cut off while facing west. Before the best of the root is dug and cut, one must dance about it while saying as much as one can about the mysteries of love. Essentially, repeating as many indecent things as possible. This refers to said that if one acts lewdly enough, it is possible to frighten demons away, freeing the root from interference with lingering spirits of malintent. It seems clear that Mandrake maintained a firm grip on the vivid images of love and lovemaking throughout history to different cultures. This love association that enabled mandrake to become associated with salacious acts in the Middle Ages. To the ancient Greeks, Aphrodite was also known as Mandragoritis “she of the mandragora”. It was one of the plants sacred to her. It was also sacred to the infamous goddess of witches, Hecate. She was both the poison goddess, and the goddess of birth and aphrodisiacs. It was said of her garden as described by Orpheus that, “Many mandrakes grow within.” Josephus Flavius ( 37 – c. 100), the Jewish historian, diplomat and general claimed this wonderful plant emitted a glowing red light at night, and that the shy plant would withdraw if it saw someone approaching. Others claimed this ghostly glow as well, and it was shortly after this time in antiquity we see the dog come into play in the story of the Mandrake. Aelian (c. 175 – c. 235 CE) instructed one to tie a starving dog to the plant and place some meat within smelling distance. The poor beast would pull the plant up, killing itself by hearing the mandrake’s ungoldy cry, and be buried afterwards in the plant’s place in a ceremony honoring the gift of life for it’s masters conquest. The shape of the mandrake is likely one of its characteristics that made it most amenable to magic. It often resembles a human being, like that of another famous root, ginseng, which also came to be known as a panacea, or cure all, of the human body. It is hard to say where the mandrake went from useful and mysterious medicinal plant to sinister homunculus. Harold Hansen postulates that it may stem from the story of Jason’s ‘dragon men’, but it is most likely from early Christianity. It was said that the mandrake was a first draft of Man that God discarded after creating Adam from the red earth of Paradise. Hence it’s eerie human-like form. The German name for mandrake is Alraune, which comes from Alrun, and may have meant, “he who knows the runes”. Germanic oracles, who were known far and wide in ancient times, would use the mandrake in concoctions to enter prophetic states. Though sadly, as Christianization overtook Europe, so too did the associations of mandrake go from seer’s plant to an almost demonic entity. It was in early Medieval Germany, new traditions and beliefs formed around the mysterious root, and perhaps brought about some of its most sinister associations. It’s folk names now included gallow’s man and dragon doll, for it was said to only grow at the base of the gallows where, in the throes of death, a hanged man’s urine or semen stained the earth. Though, in Denmark, it could not just be any man, but a “pure youth” or “right lad”. Someone destined from birth, through bearing the misfortune of being born to a woman who stole while pregnant. It was believed that if a woman stole while pregnant her sons would be scoundrels and thieves and her daughters whores. Others took it to mean a man wrongly hanged and chaste. Either way, it was a rare and strange occurrence for a mandrake to be born. Many would pay high prices for the mandrake, for it practically did it all. Luck in love, healed the diseases brought about it, brought in wealth and acted with a power no woman could resist. To convince the root to do these things for you, however, required careful action, for the Mandrake still bore hatred for mankind for being chucked aside as a prototype on God’s drafting desk. It must be bathed in wine, wrapped in red or white silk cloth as well as a little velvet cloak. It must also be fed. What to feed it varied depending on who you asked. These roots continued to be known as “alruna” or “alraunes” in Germany and England. Communion wafers saved in the mouth from Church, spittle from a fasting person, or even earth from Paradise. Even with the best care, however, sometimes the Mandrake would tire of its owner and stop working. In these instances they had to be sold right away, unless they turn the tides and cause misfortune for their masters. Interestingly, it could only be sold for less than one had bought it for, and if the owner died, it must go to the grave with them and be prepared to be judged along side them at heaven’s gates. These mysterious fetishes are simply roots from certain plants fashioned into the shape of a human to be used for magical purposes, but the often human-shaped mandrake is the inspiration for this strange and wonderful practice. In Medieval England, these charms were known as “alrunen”. In Germany during the same era, the “alruna” were so revered that they were dressed everyday lest they do their owners harm. They have lived on in German and English folklore where it was said that well-kept alraune were dressed in silk and velvet and ‘fed’ meals of milk and cookies. Dr. Faust himself was said to have an alraune. In 1888, it was said such ‘manikins” could be found among the Pennsylvania Dutch. In Renaissance era magic it was also, like henbane, used as a magical incense associated with the moon and placed under the pillow for prophetic dreams. Hildegard von Bingen, a 12th century herbalist, abbess and visionary mystic, was one of the first to record her criticisms of the mandrake: “With this plant, however, also because of it’s similarity to a person, there is more diabolical whispering than with other plants and it lays snares for him. For this reason, a person is driven by his desires , whether they are good or bad, as he also once did with the idols...It is harmful through much that is corruptive of the magicians and phantoms, as many bad things were once caused by the idols.” Yet she also prescribed its use, still paying homage to the powerful plant for depression of sorts that he should place a spring-washed mandrake root whole with him in his bed while he sleeps. There is even a little charm that accompanies it, though Hildegard would have never called it such, “God, who makes humans from the dirt of the earth without pain. Now I place this earth, which has never been stepped over, beside me, so that my earth with also feel that peace which you have created.” (Physica 1.56). +Constituents+ It contains the potent alkaloids scopalamine, hyoscyamine, atropine, apoatropine, and many more. The effects are little written about despite the popularity and notoriety of this root. It is poisonous but less so than our other solanaceae friends. +Bibliography+ Agrippa, Henry Cornelius. The Philosophy of Natural Magic. L. W. de Laurence ed. 1913. Originally published in 1531-3, De occulta philosophia libri tres, (Three books of Occult Philosophy) proposed that magic existed, and it could be studied and used by devout Christians, as it was derived from God, not the Devil. Agrippa had a huge influence on Renaissance esoteric philosophers, particularly Giordano Bruno. Bevan-Jones, Robert. Poisonous Plants : A Cultural And Social History. Oxford: Windgather Press, 2009. Friend, Hilderic. Flower Lore. Rockport, MA: Para Research, 1981. Hansen, Harold A. The Witch's Garden. York Beach: Samuel Weiser, 1983. Print. Höfler, Max. "Volksmedizinische Botanik Der Germanen." 1908. Hyslop, Jon, and Paul Ratcliffe. A Folk Herbal. Oxford: Radiation, 1989. Jiménez-Mejías, M.E.; Montaño-Díaz, M.; López Pardo, F.; Campos Jiménez, E.; Martín Cordero, M.C.; Ayuso González, M.J. & González de la Puente, M.A. (1990-11-24). "Intoxicación atropínica por Mandragora autumnalis: descripción de quince casos [Atropine poisoning by Mandragora autumnalis: a report of 15 cases]". Medicina Clínica. 95 (18): 689–692. Moldenke, Harold N. and Alma L. Moldenke. Plants of the Bible. New York, NY: The Ronald Press Company, 1952. Netter, M. W. "The "Mandrake" Medical Superstition." The Medical Standard. Vol. III. Chicago: G.P. Englehard, 1888. 173-75. Perger, von K. Ritter. 1864. Deutsche Pflanzensagen. Stuttgart and Oehringen: Schaber. Raedisch, Linda. Night of the Witches: Folklore, Traditions & Recipes for Celebrating Walpurgis Night. Woodbury, MN: Llewellyn Publications, 2011. Raitsch, Christian. The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants Ethnopharmacology and Its Applications. Rochester, VT: Park Street, 2005.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

April 2024

To support me in my research and work, please consider donating. Every dollar helps!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed