Passing Through the Brambles: Blackberry in Appalachian Folk Magic

Even though the land is covered in ice, I’m thinking about Blackberries. I see their reddish arching canes along the frosted, crunching earth as I traverse the winding roads of Madison County, North Carolina where I live. As a person of predominantly North Atlantic Islands and Germanic ancestry the blackberry both feels like a plant rooted in my ancestors folklore, as well as a common and abundant plant in my bioregon of Appalachia. As I focus on rebuilding my shop destroyed in Hurricane Helene, I am finding joy in taking moments to reminisce about my favorite plants in my Appalachian folk magic practice and those I work with most. Blackberry definitely has my heart.

Blackberries (Rubus spp.) grow throughout the Northern parts of the world, and Appalachia is no exception. Here in Appalachia there are the native (Rubus alleghaniensis) Allegheny blackberry, (Rubus canadensis) American dewberry, (Rubus flagellaris) trailing blackberry, (Rubus frondosus) common blackberry, and (Rubus recurvatus) Southern dewberry among many other native Rubus species. Sometimes, these Rose family members hybridize occasionally making exact species identification difficult.

We also host many invasive and non-native species like the abundant Himalayan blackberry (Rubus armeniacus). While all species are not toxic and safe to use for food and medicine, the non- natives species have become ecologically damaging. I notice the Himalayan species as they have white undersides to their leaves and a star-shaped cross section when you cut their canes, which are green-red with large thorns. White they are here, I will focus my attention on harvesting and using the invasive species.

Blackberries often grow thick in old fields and on forest edges. They are truly a plant of the hedge, sometimes they are the very backbone of it. Bramble patches, while pesky to move through when trampling about looking for herbs, are one of the most well loved medicinal and magical plants in the mountains. Their sharp thorns and sweet fruits position them at the gateway of both gentle and fierce. If you are unlucky enough to get tangled up in their thorns, you’ll see why they are a plant that my friend Corinne Boyer would remind us, is truly of the Devil.

According to the well known Southern folk herbalist, Tommie Bass of Alabama, next to peach leaves, no other herb has such a distinguished use in the South. Their high tannin content of their roots and leaves makes them useful for skin ailments, sores, sore throat and vomiting due to their astringency. They shine as a remedy for diarrhea and dysentery, or the “summer complaint” as it was once known, especially the tea of the roots due to this medicinal action.

To make blackberry root tea in the Appalachian folk medicine way, take a teacup full of roots to a quart of water and boil for 20 minutes. Strain and take a swallow of the tea every time you have to run to the restroom to help deal with the “summer complaint” as they used to call it. You can also make tea with the rest of the plant: leaves, flowers and berries. Take one teaspoon of dried leaves to one cup of water. To make tea with the roots use one teaspoon of dried or powdered roots or the same of green fruits, fresh or dried to one cup freshly boiled water. Blackberry jam and even the wine of the berries are both old remedies for “the trots”. If diarrhea persists however, ensure you see a doctor as it can be very serious.

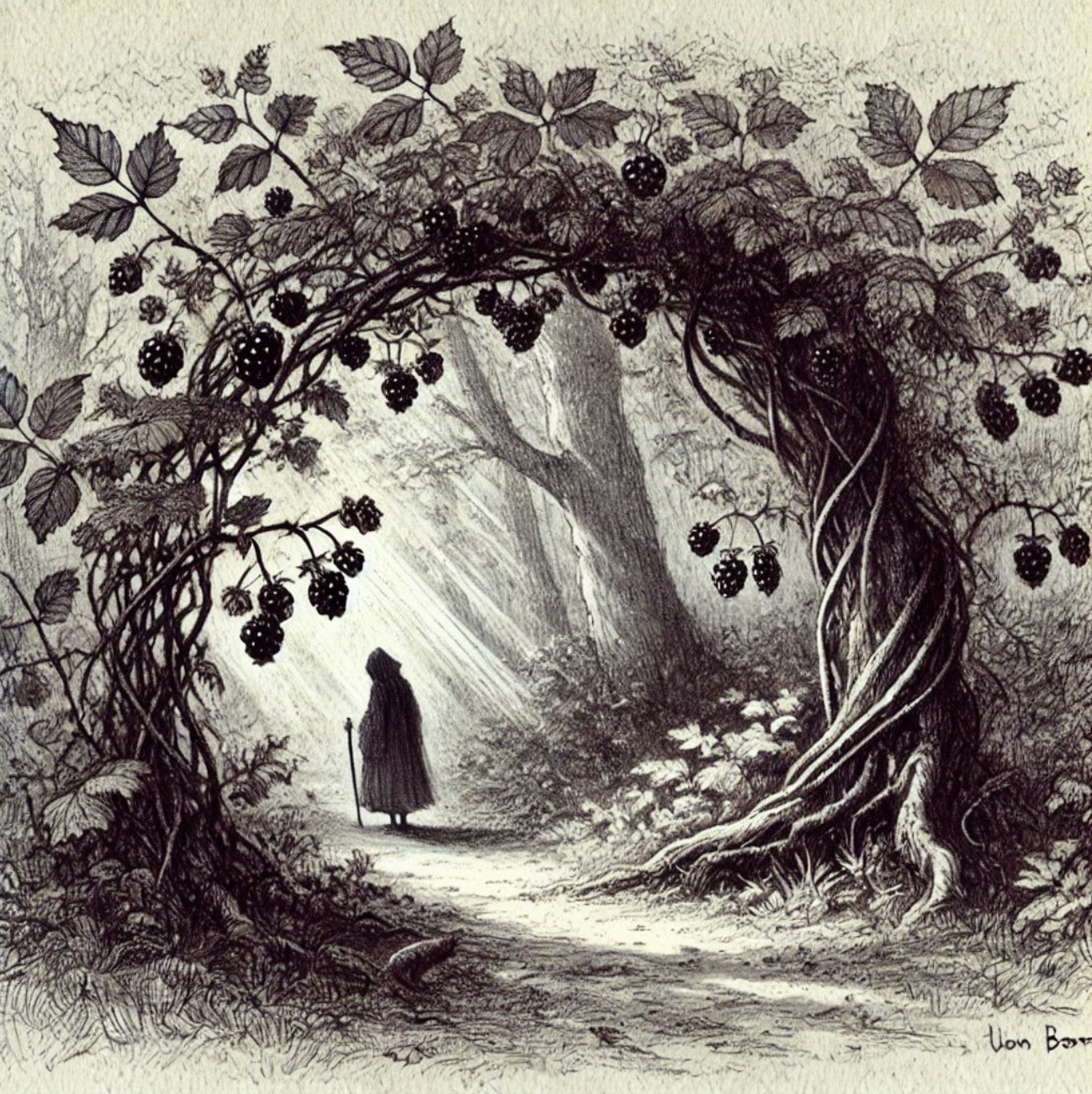

This thorny plant is involved in one of our most curious healing magics in Appalachia as well. The act of “passing through”. This is the magical act of passing a child or adult through a natural hole created by either a tree, plant or human-made object. Passing through rituals have used, aside from briars, horse collars, holes in trees, white oak sapling splits and even the “circular” space created by passing a child under the belly of a standing horse or donkey.

The act of passing through may be a remnant of notions of purification of blood guilt in ancient times by forcing individuals, or whole armies, to pass under gates or yokes, by which act they were "stripped," as it were, of attached stigma. It is an imitation of a form of divestment or removal of a spiritual, physical or simultaneous condition. A bramble portal to pass through, if you will, where you emerge, cleansed on the other side.

Essentially a stand of briars were made to resemble a passageway by burying the exploratory shoots of these prolific vining plants and making a sort of tunnel. Due to the amazing growth habit of Blackberries, the buried shoots will take root and form a true and natural tunnel. This is called "air layering" in plant propagation. This circular space was then used magically as the portal to “pass through” sick children, people and objects to cure them of specific illness like hernia, or end bewitchments.

In North Carolina, a folk cure for whooping cough was to place the diseased person under a briar whose end has taken root in the ground. A similar cure for a child or adult with whooping cough would be performed by having the patient crawl under the bush 3 times forward and back, or if a young child, they would be passed back and forth beneath this natural passageway.

Sometimes the cure would be further added to by giving tea of the blackberry roots from the very bush you were passed through to effect the cure. Blackberry is also an important part of Indigenous medicine traditions in Appalachia and the uses mirror those around the world. Root decoctions are made for sore eyes, gastrointestinal issues, and many other treatments where an astringent was called for.

There is also strange lore that the blackberry blossoms mean death is sure to come in Appalachia. This is a curious thing and I wonder often if this is the diabolical association between the Devil and the blackberry.

The witches whisk I made of blackberry canes, as I learned from the works of Gemma Gary with Iron nail charms of my making.

Much of the lore of blackberries in Appalachian folk magic today comes from the ways brought over by English, Scottish, Irish, Welsh and Germanic settlers. However some lore remained in the North Atlantic Islands alone:

In England, on St. Simon and St. Jude’s Day (October 28th), tradition says that Satan sets his foot on the Bramble, after which, it is said not a single edible Blackberry can be found. In Sussex, England, they say that, after Old Michaelmas Day (10th October), or today, the 29th of September, the Devil goes round the county and spits on the Blackberries, making them sour and poisonous. He especially hates them as it is said he was cast into their thorns on his fall out of Heaven.

In Scotland, it is thought that late in the Autumn, the Devil throws his cloak over the Blackberries, and renders them unwholesome. In Ireland, there is an old saying, that “at Michaelmas the Devil put his foot on the Blackberries;” and in some parts of that country folks will tell their children, after Michaelmas Day, not to eat the sméar dhubh (Blackberry); and they attribute the decay in them, which about that time begins naturally, to the operation of the Púca, a mischievous goblin, sometimes assuming the form of a bat or bird, at other times appearing as a horse or goat.

Elsewhere in Western Europe, both the fruit and flowers of the Bramble were believed to be healing to the bites of serpents; and it was at one time believed that so astringent were the qualities of this bush, that even its young shoots, when eaten as a salad, would fasten teeth that were loose.

John Gerarde, however, for that purpose recommends a decoction of the leaves, mixed with honey, alum, and a little wine, and adds that the leaves “heale the eies that hang out.” In Cornwall, Bramble leaves, dipped with spring water, are employed as a charm for a scald or burn. The moistened leaves are applied to the burn whilst the patient repeats the following formula:--

“There came three angels out of the East,

One brought fire, and two brought frost;

Out fire and in frost;

In the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.

Amen.”

Today we see the remnants of this charm in our mountains as the prayer used by many Appalachian burn whispers of all races:

"There came two angels from the north ; / One brought fire, and one brought frost. / Go out fire and come in frost." This is usually repeated three times while blowing on the burn and either passing the hand from heart outwards on the patient followed by

+ + +

meaning the Father, Son and Holy ghost three times.

This is just a tiny toe into the world of blackberry and their magic, especially here in Appalachia. I feel the world swirling with chaos, but today I am taking a moment to comfort myself with the Blackberry: thorns that catch and the claws that snatch. Blackberry, the portal maker, the astringer, the rich, antioxidant purple juiced blood builder. Hail the Blackberry, ᎧᏄᎦᏟ in Cherokee, ʃpa in Yuchi, just some of the many first names for this being spoken in this special place.

Works Cited:

Skinner, C. M. (1911). Myths and Legends of Flowers, Trees, Fruits, and Plants in All Ages and in All Climes. United Kingdom: J.B. Lippincott.

White, N. I., Belden, H. M., Brown, F. C., Brewster, P. G. (1952). The Frank C. Brown Collection of North Carolina Folklore .... United States: Duke University Press.

Vickery, R. (2010). Garlands, Conkers and Mother-Die: British and Irish Plant-lore. United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 9