Cauld Iron: Iron in Appalachian Folk Magic

The Winter Solstice is upon us. It’s a busy time, and I’m looking forward to some rest which unfortunately has come in the form of COVID. It’s a good time to reflect on what must be done. It’s time to sharpen the tools that we used all year and fix the scythe that’s broken.

Metal tools are such a blessing. It’s wild to think about how our ancestors and the ancestors of this land in Appalachia made due before the advent of metal tools. It must have felt miraculous, that first spark of iron on stone. A power so mighty it would take your breath away. Iron has been revered and even slightly feared around the world in magic and folklore, and it’s not hard to imagine why.

Iron is the most common element on Earth by mass. Isn’t that wild? When you begin to delve into folklore, whether as a formal study or a cozy pastime, you find that all around the world Iron has deeply magical properties. Every culture that has used iron significantly has stories of it protecting against fairies, keeping away demons or fighting evil in some way. Folk memory has shaped how tools were made and interpreted, from magical swords to cursed objects.

Pliny the Elder, ancient Roman natural philosopher, mentions iron as a medicinal and magical substance around 79 CE:

"Iron is employed in medicine for other purposes besides that of making incisions. For if a circle is traced with iron, or a pointed weapon is carried three times round them, it will preserve both infant and adult from all noxious influences: if nails, too, that have been extracted from a tomb, are driven into the threshold of a door, they will prevent night-mare."

Pins and nails were used in Ancient Greece and Rome for magical purposes, and eventually this practice spread or sprung up throughout Western Europe and even into the Americas (1). We see the survival of this powerful belief in the magical uses of iron all the way into the American south with the use of coffin nails in Hoodoo and in Appalachian and Ozark folk magic.

The inherent magic of iron has mysterious roots and one theory is that its magnetism was somewhat responsible. There were certain taboos about using new metals as the Bronze age gave way to the Iron. Animistic religious beliefs held conservatively to their old metals and had a general reluctance to move to a working with a new metal. This was due to a world that was more widely seen to be inhabited by spirits that could punish humans if displeased. A metal that can move other metals, imagine how it would be to see that as a Bronze Age human? It’s incredible to ponder.

There was mention that Roman priests could only shave with bronze and not iron due to these taboos, as well as certain members of the royal class being unable to touch iron. It’s interesting to see how this parallels the Irish belief that the Sidhe or Fae cannot touch iron. This metal has both a protective influence as well as a feared “newness” that has persisted in folk memory throughout many nations, expressed through the lore of foregoing iron for certain purposes. Many plant harvesting traditions forbid a blade of iron to cut them. In Scotland, when scapulamancy is performed (the art of diving from a shoulder blade), an iron blade cannot be used (2).

Iron revered for its magic into the Middle Ages as a preventative against witchcraft. In medieval Ireland, it was said the magic of iron came from the power of St. Patrick and his blessings, and in Ireland, found horseshoes are the best to hang about the home to protect it from evil.

“On threshold that the house might be,

From Witches, thieves and divels free,

For Patrick O’er the iron did pray,

And made it holy, as they say.”

-History of Ireland in Verse (1750)

Elsewhere in the North Atlantic Islands, plunging a hot iron into bewitched milk would surely undue an enchantment cast on an unlucky cow. In England, people used “cauld iron” or cold iron from cast off horse shoes, old scythe blades and other tools to hang about barnyards to keep their horses safe from the riding of night hags(3). In witch bottles, or obscured and hidden glass bottles full of protective objects or substances, iron pins were by far the most common element found in over 200 bottles examined (4).

The blacksmith was also believed to be inherently magical, even infernal, in their ability to bend the hardest substances humans knew of at the time with the mystery and danger of fire. From Stephanie Rose Bird, Ogun is a warrior Orisha in Yoruba, Ifa, Lucumi and Santeria traditions and spiritual paths. He is a fire being and a metalurgic master. He shares much magical iconography as a Smith and metal worker. He is also a God of Iron. Anvil dust, rusted nails, railroad spikes and coffin nails are used extensively in Hoodoo and other African based traditions showing the world wide influence iron has had on the folk magic of nearly every nation (5).

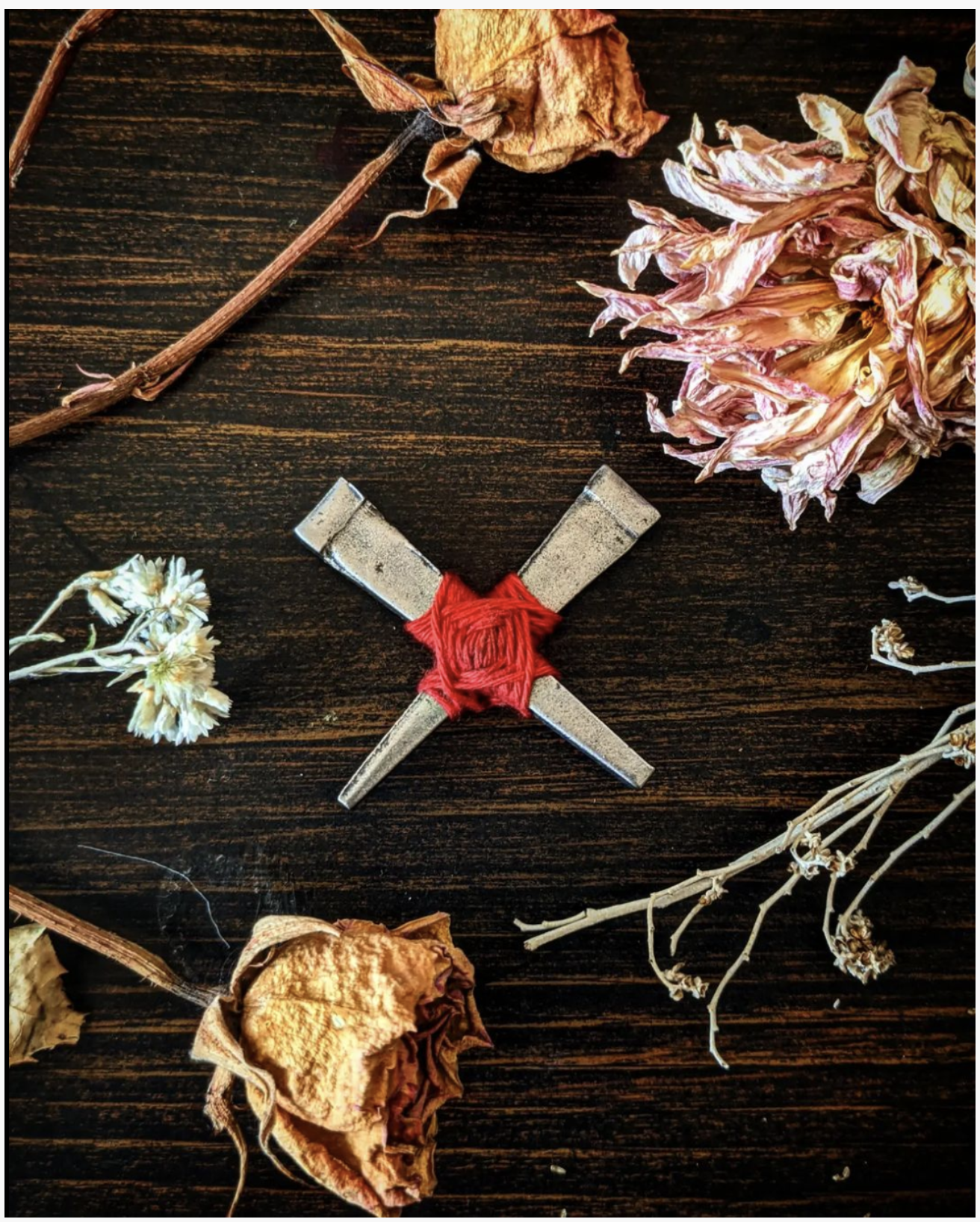

Railroad spikes of iron also have come to be an important part of Hoodoo. The ritual of ‘nailing it down’ comes from more modern Rootwork traditions, but its essence is much older and is an amalgamation of diverse cultural influences. Generally, it is used to ensure no one shall cause you to move from your land, yet it can be used for many purposes. Placing an iron railroad spike at the quarters of a home, property or garden can act as a magical boundary line, keeping that which we want in and that which we do not out. Small iron nails were also driven into the corners of the ceilings of rented homes for the same purpose by tenant folks in the South historically to prevent landlords from outsing them.

In Appalachia, iron was used extensively in folk magic and medicine. It retained many European Old World magical beliefs and of course was augmented by the unique geography that this place provided as well as the Indigenous inhabitants of the mountains and enslaved African peoples brought here by force each had of their own. In Appalachia, iron nails were used both as internal medicine for iron in the blood as well as for charms.

To be exact, iron nails soaked in vinegar were used to make a tonic for the blood (don’t do this now!) In Kentucky, witch bottles much like the ones found in England, were discovered to contain iron nails and pins, often bent, to protect stable and home from malefic forces (6). Nails are also used in Appalachian folk magic to cause someone to wither away by dropping them into their unworn shoes, and the remedy to this was to gather up all the loose nails around a property of the afflicted and bury them under a hickory tree off their property.

Iron horse shoes were also hung over doors to prevent witchery and evil spirits from entering home or stable. There is one theory that the ancient surgeon, with their metal tools, would cut the boil or afflicted part and the pus or infection would leave, in a manner it drove out the infection visually, appearing to wed the as above, so below of magically charming, or driving out an illness with “cauld iron”. (7)

As a person who cooks in cast iron most days, I am constantly reminded of the magic of iron as we bake our acorn cake and fry our home grown potatoes. The ability to transform metal into a tool is truly fantastical and it makes sense to me why metalworking has been held in such a high magical degree for so long. With so many smiths as friends I feel comforted by their magical ways as I mince my garlic with a cleaver forged by one friend and chop my magical herbs with a boline made by another. On these cold days leading up to Twelfth Night I shiver at the touch of iron and wonder at its long history of magic and medicine. I look at the horseshoes and wool shears above the door and take solace in their longstanding power to cut as the spirits of illness and mayhem roam the land in the icy air.

Blessings on you and yours this Midwinter time and take care.

Smith friend Asa Hewlette of @theshinginggrain working iron at a Goblin Market years ago! He has made many of my knives.

Works Cited:

(1). Pennick, Nigel. Pagan Magic of the Northern Tradition: Customs, Rites, and Ceremonies. United States, Inner Traditions/Bear, 2015.

(2).Frazer, James George. The Golden Bough: Taboo and the perils of the soul. United Kingdom, Macmillan, 1914.

(3). Houlbrook, Ceri, and Davies, Owen. Building Magic: Ritual and Re-enchantment in Post-Medieval Structures. Switzerland, Springer International Publishing, 2021.

(4). Hidden Charms Transactions of the Hidden Charms Conference 2016. Edited by John Billingsley, Jeremy Harte and Brian Hoggard.

(5).Bird, Stephanie Rose. Sticks, Stones, Roots & Bones: Hoodoo, Mojo & Conjuring with Herbs. United States, Llewellyn Publications, 2004.

(6). Manning, M. Chris. “The Material Culture of Ritual Concealments in the United States.” Historical Archaeology, vol. 48, no. 3, Society for Historical Archaeology, 2014, pp. 52–83.

(7) Robert Means Lawrence. The Magic of the Horse-Shoe. 1898. Chapter 6, Iron as a Protective Charm.